Jollof rice can feel like a whole region in one pot. Rice cooks in a deeply seasoned tomato base, onions soften, peppers bring warmth, oil carries flavor, and the kitchen starts to smell like a gathering is coming.

Table of Contents

ToggleOn paper, the dish looks simple. In real life, the story stretches across empires, trade routes, colonial-era food shifts, and modern cultural pride.

Jollof shows up as everyday lunch, wedding food, street food, comfort food, and a loud, funny argument you can start in seconds at any West African gathering.

What follows is the long version. Where jollof likely began, how it moved across borders, why it looks and tastes different from one country to the next, and how the Jollof Wars became a real cultural phenomenon rather than a meme.

What Counts as Jollof, and Why It Matters So Much

At its core, jollof is one-pot rice cooked in a seasoned, reddish sauce built from tomatoes, onions, peppers, and fat. Tomatoes can arrive fresh, puréed, pasted, or mixed.

Fat usually means vegetable oil, sometimes butter. From that base, every country, city, and household adds logic of its own. Rice choice, spice blends, cooking order, proteins, vegetables, and final texture all vary.

High-authority references describe jollof as West African, with the name tied to the Jolof, or Wolof, Empire. Early roots sit in the Senegambia region.

That origin matters culturally as much as it does historically. Jollof often carries the role of celebration food, the dish that feeds a crowd and signals hospitality. When a pot of jollof appears, people assume an occasion is happening.

Origins: The Senegambia Foundation and the Wolof Connection

The strongest written trail leads back to the Wolof world. Encyclopaedia Britannica traces jollof to the 14th-century Wolof empire, where rice cultivation supported grain-centered meals and shared eating traditions. The linguistic link between “Jolof” and “jollof” reinforces that connection.

Wolof food culture relied on communal eating and rice-based dishes that carried flavor through broth, vegetables, and protein. That structure shows up clearly in early jollof ancestors.

Saint-Louis and the Ceebu Jën Origin Story

For a formal anchor point recognized globally, UNESCO offers one of the clearest records. UNESCO lists ceebu jën, often written thieboudienne, as originating in the fishing communities of Saint-Louis, Senegal. The dish features fish, broken rice, vegetables, and a tomato-forward seasoning.

That recognition matters for two reasons. It supports Senegal’s claim as the homeland of a foundational jollof ancestor.

It also frames the dish as cultural heritage rather than a casual recipe. UNESCO emphasizes variation by region while highlighting core elements that remain recognizable across households.

Why Modern Jollof Looks the Way It Does

Even with deep roots, modern jollof could not exist in its current form thousands of years ago. Ingredients tell that story clearly.

Tomatoes and Peppers Changed Everything

The red base associated with most jollof depends on tomatoes and peppers that arrived from the Americas and spread globally over time.

Once those crops became widely available and affordable, cooks across coastal West Africa leaned into them. Many food historians argue that the tomato-forward style most people recognize today likely took shape in the 19th century or later.

Colonial Agriculture and Imported Rice

Colonial-era shifts in agriculture and trade reshaped West African diets. Imported rice varieties entered local markets. Cash-crop economies altered what people grew and bought.

Jollof adapted to those changes, becoming a flexible, efficient way to turn rice into a full meal. The dish stayed useful because it absorbed new ingredients without losing identity.

How Jollof Spread Across West Africa

Jollof did not become iconic by staying frozen. It traveled, adapted, and stayed practical.

Trade Routes and Shared Cooking Logic

Across West Africa, dishes appear under different names while sharing clear DNA. Benachin, riz au gras, zaamè, and related rice dishes follow similar one-pot logic.

Many food historians describe jollof as “mutually intelligible” across borders. Someone familiar with one version can usually recognize the structure elsewhere.

Rice Became Central to Urban Diets

Rice consumption expanded dramatically across the region during the 20th century. Reporting from the Food and Agriculture Organization shows long-term growth in per-capita rice consumption.

One FAO document notes that average per capita rice consumption in West Africa rose from 12 kg/year in 1961 to 27 kg/year in 1990, a 125% increase during that period.

Another FAO update projects African rice consumption rising to 34.9 million tonnes of milled rice by 2025. When rice becomes more central, rice dishes that feed many people efficiently gain power. Jollof fits that role perfectly.

The Major Jollof Variations, and What Shapes Each One

Jollof changes with rice type, heat level, aromatics, cooking method, and texture goals. Some versions chase smoky dryness. Others lean softer and stew-like. Each reflects local preference and pantry reality.

Senegal: Ceebu Jën (Thieboudienne)

Senegalese ceebu jën centers on fish, broken rice, and vegetables such as carrots, cabbage, cassava, and eggplant.

UNESCO highlights fish steak, dried fish, molluscs, seasonal vegetables, and aromatics like garlic, parsley, chili, and tomato.

Flavor goal stays savory and deep, with ocean richness. Texture aims for grains that remain distinct while soaking up stock and vegetable flavor. Tomato sweetness often plays a smaller role compared to some coastal red jollofs.

The Gambia: Benachin

In The Gambia, benachin often translates loosely as “one pot.” The philosophy matches jollof closely. Fish or meat appears depending on region and household.

Flavor goal leans balanced and hearty, built for family meals. Texture stays soft without sliding into mush.

Nigeria: Home Jollof and Party Jollof

Nigerian jollof carries a reputation for bold seasoning and heat. Many cooks favor parboiled long-grain rice, rinsed, parboiled, and steamed so grains hold up under heavy sauce.

Party jollof stands apart. Cooked outdoors over firewood, it chases smoky aroma and a slightly toasted bottom layer that guests argue over.

Flavor goal focuses on pepper intensity and depth, with smoke playing a role at celebrations. Texture stays dry enough to keep grains separate.

Ghana: Jasmine Rice Pride

Ghanaian jollof often features Thai jasmine rice or other fragrant varieties. Rice choice shapes the entire experience. Jasmine brings aroma and tenderness.

Flavor goal stays aromatic and balanced, with spice present but not overwhelming. Texture aims for soft, fragrant grains that lead the experience.

Sierra Leone and Liberia: Everyday and Celebration Jollof

In Sierra Leone and Liberia, rice plays an enormous role in daily eating. FAO documents note that in some West African countries, per-capita rice consumption exceeds 100 kg per year, including Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Jollof appears as everyday food and celebration food, paired with local proteins and sides.

Flavor goal leans comforting and adaptable. Texture often skews home-style and slightly softer.

Francophone West Africa: Riz Au Gras

Across many French-speaking countries, a close cousin appears as riz au gras, literally “fat rice.” Vegetables often take a larger role, and the rice type varies.

Flavor goal emphasizes savory richness and vegetables. Texture can feel heartier and slightly stickier depending on the rice choice.

Cameroon: Hybrid Influences

Some Cameroonian versions resemble seasoned rice with mixed vegetables, sometimes described casually as “fried rice.” The structure still follows jollof logic.

Flavor goal highlights spice and vegetable contrast. Texture stays drier and mixed, with less sauce.

Quick Comparison Across Borders

| Region or Name | Typical Rice | Base Flavor Profile | Common Proteins | Texture Vibe |

| Senegal (Ceebu Jën) | Broken rice | Fish-stock savory, tomato and veg | Fish, dried fish, molluscs | Infused, hearty |

| Nigeria (Jollof) | Parboiled long-grain | Pepper-forward, smoky at parties | Chicken, turkey, beef, goat | Separate grains, slightly dry |

| Ghana (Jollof) | Jasmine rice | Aromatic, balanced spice | Chicken, goat, beef | Tender, fragrant |

| Francophone (Riz Au Gras) | Varies | Rich, vegetable-forward | Chicken, beef, fish | Hearty, “fat rice” |

| Gambia (Benachin) | Long-grain | Balanced, home-cooked | Fish or meat | Comfort-soft |

How Rice Became a Regional Rivalry

Spend time around West African social media and the argument appears quickly. Who makes the best jollof.

The modern Jollof Wars gained momentum during the 2010s, especially between Nigeria and Ghana. Cook-offs, memes, and friendly insults spread online and offline. Beneath the jokes sits real cultural pride.

The Jamie Oliver “Jollofgate” Moment

One flashpoint arrived in 2014, when Jamie Oliver published a jollof rice recipe that included ingredients many West African cooks considered completely off-base. The hashtag #jollofgate followed, along with widespread criticism.

The reaction reflected more than internet humor. Jollof functions as cultural property. People respond strongly when the dish feels rewritten without context.

World Jollof Day and Global Visibility

Diaspora restaurants, food media, and online campaigns pushed jollof into global awareness. “World Jollof Day” circulates online, and jollof received a Google Doodle in 2022, marking recognition beyond West Africa.

When Rivalry Hits Real Life

The rivalry even appears in sports banter. Nigeria versus Ghana football matches sometimes earn the nickname “Jollof derby,” showing how food rivalry became shorthand for broader cultural competition.

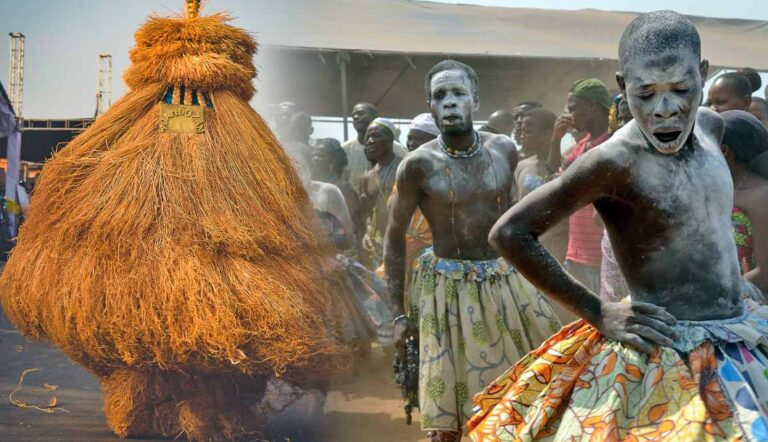

Parties, Hospitality, and Memory

Jollof carries emotional weight. Food historian Ozoz Sokoh describes the dish as central to birthdays, funerals, weddings, and celebrations. That role repeats across major writing on the topic.

In many Nigerian contexts, jollof functions as cultural shorthand. Serving good jollof signals good hosting. The pot itself suggests something joyful or communal is happening.

Why Jollof Costs More for Some Families

Jollof also offers a window into economics. The dish relies on rice, tomatoes, peppers, cooking oil, and protein. Prices for those ingredients can spike.

Recent reporting in the UK press described how jollof has become harder to afford for many Nigerian households during inflation.

A “Jollof Index” estimated the cost of cooking a pot for a family of five, noting how some families shift toward simpler “concoction rice” when full jollof becomes expensive.

Rice demand across Africa continues to rise, and many countries remain net importers. Currency shifts and trade conditions can ripple directly into the pot.

What Makes Great Jollof in Practice

Across borders and rivalries, experienced cooks tend to agree on fundamentals.

Cook the Base Properly

The tomato, pepper, and onion base must cook long enough to lose raw edges and taste integrated. Rushing here shows immediately.

Choose Rice With Intent

Parboiled long-grain stays firm and separate, ideal for large pots.

Jasmine rice brings fragrance and softness, common in Ghanaian cooking.

Broken rice suits Senegalese ceebu jën, soaking up stock and fish flavor.

Balance Heat Carefully

Heat should feel alive without overpowering tomato sweetness and savory depth.

Treat Smoke as an Ingredient

Outdoor party jollof gains obvious smoke. Indoor cooking often chases toasted notes at the bottom of the pot, a prized layer many people fight over.

Respect Scale

Jollof scales from quick dinner to feeding 100 people without losing identity. That flexibility explains much of its staying power.

Who Owns Jollof

The cleanest answer points to shared heritage with strong historical roots in the Senegambia region. UNESCO’s recognition of ceebu jën establishes a formal heritage claim for a foundational ancestor. Britannica situates its early roots in the Wolof empire.

At the same time, jollof belongs to the entire region. West Africans across borders adjusted the dish to local rice, peppers, budgets, and party culture. That adaptability built its reach.

Summary

Jollof rice is history you can taste. The dish carries traces of the Wolof world, Senegal’s fishing communities, regional trade and migration, changing rice economies, and modern cultural identity.

Rivalry makes it louder. The deeper story stretches far beyond Nigeria versus Ghana. Jollof remains a shared West African language, spoken in rice.

Related Posts:

- Traditional Jollof Rice Recipe - Flavorful and Simple

- History of the Ashanti - Empire and Colonization

- Senegal National Football Team History, Key Players,…

- Ivory Coast National Football Team - History and…

- The Fulani People – History, Culture, and Tradition

- How the Songhai Empire Shaped West African History