West Africa supported powerful and advanced urban societies long before European colonization reshaped global history.

Table of Contents

ToggleLarge cities operated as political centers, trade hubs, and cultural anchors, yet later narratives minimized or erased their presence.

Urban planning, long-distance commerce, and systems of governance developed over centuries, shaping societies that interacted with North Africa, Europe, and the wider world.

Silence surrounding these cities says more about historical bias than about African achievement.

1. Benin City

Power, planning, and continuity defined Benin City during centuries of Edo rule. Functioning as the political and ceremonial heart of the Edo Kingdom, Benin City reached prominence between the 11th and 15th centuries.

Governance relied on a centralized monarchy supported by titled officials, craft guilds, and ritual authorities.

Early European observers expressed surprise at the civic order that contrasted sharply with stereotypes applied to African societies.

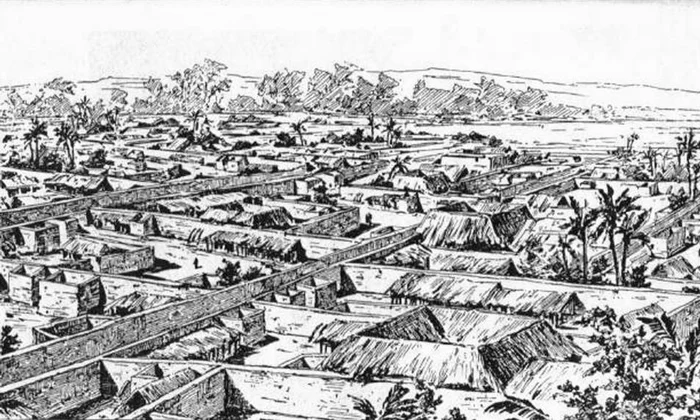

Accounts described an urban center organized with intent rather than chance. Roads extended in straight lines, districts followed regulated patterns, and royal authority enforced maintenance and security.

Stability across generations allowed institutions to mature without constant disruption.

Urban Marvels

Urban design in Benin City reflected mathematical planning and environmental knowledge. Defensive and administrative structures worked together across a vast area, demonstrating long-term coordination.

Scale becomes clearer through key physical features that shaped daily life.

Key elements included:

- Benin Moats is forming an earthwork network exceeding 16,000 kilometers

- Defensive walls paired with ditches controlling movement and access

- Street systems are aligned in repeating geometric patterns similar to fractal design

Construction relied on human labor, local materials, and inherited engineering knowledge. Coordination required a centralized authority capable of mobilizing communities over long periods.

Art and Culture

Cultural production reinforced political power and historical memory. Craft guilds operated under royal patronage and followed strict apprenticeship systems. Artistic output served ceremonial, religious, and archival purposes rather than decoration alone.

Objects later labeled Benin Bronzes recorded rulers, court rituals, diplomatic encounters, and spiritual beliefs. Materials included bronze, ivory, and wood, each associated with status and symbolism.

Oral performance complemented visual art, ensuring continuity of history through praise poetry, ritual speech, and collective memory.

Contact With Europeans

Portuguese sailors reached Benin City during the 15th century and encountered a confident state engaged in regulated exchange.

Trade operated under royal supervision rather than foreign control. Goods moved along established channels connecting interior regions to the Atlantic coast.

Primary exports involved:

- Pepper is valued in European markets

- Ivory is used for luxury objects

- Palm oil serves multiple commercial uses

Diplomatic interaction occurred through formal audiences and negotiated terms. Edo rulers maintained authority over access and pricing, reflecting political independence during early contact.

Destruction and Colonial Violence

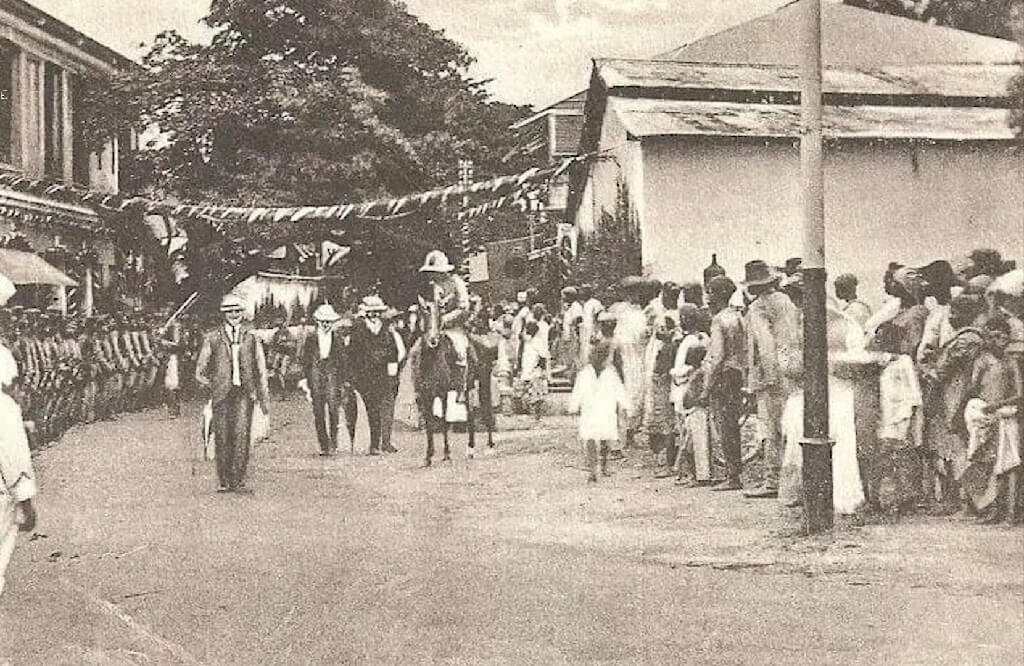

Colonial expansion ended centuries of autonomy through force. British troops invaded Benin City in 1897 following an ambushed expedition.

Retaliation is aimed at punishment and domination rather than negotiation.

Assault involved systematic destruction. Buildings burned, leaders faced exile, and sacred objects faced seizure. Thousands of artworks entered European collections, detached from their cultural context.

Political institutions collapsed under imposed colonial rule, leading to the historical marginalization of Benin City within global narratives.

2. Kansala

Memory preserved Kansala long after physical structures disappeared. Kansala served as the fortified capital of the Kaabu Empire, located in present-day Guinea-Bissau.

Kaabu emerged through westward expansion connected to the Mali Empire and remained influential between the 13th and 19th centuries.

Military organization and fortified settlements supported authority across trade corridors linking forest zones and savanna regions.

Power depended on control rather than mere occupation. Fortifications protected leadership, stored resources, and signaled dominance to rivals and allies alike.

Griot Testimony and Oral History

Historical knowledge survived through griots tasked with preserving collective memory. Boubacar Barry transmitted detailed accounts of Kansala through spoken tradition passed across generations.

Narratives described city walls, royal succession, ceremonial practices, and warfare.

Academic skepticism often dismissed such material as folklore. Written documentation received preference despite the absence of external records addressing local history. Oral transmission faced marginalization despite consistency and depth.

Archaeological Confirmation

Excavation efforts beginning in the 2010s transformed the debate surrounding Kansala. Archaeologists uncovered material evidence supporting long-held oral accounts. Physical remains aligned closely with descriptions maintained by griots.

Findings included:

- Fortification remnants matching the described wall dimensions

- Pottery fragments indicating long-term habitation

- Weapons consistent with regional warfare practices

Material confirmation demonstrated accuracy sustained through spoken memory across centuries.

3. Koumbi Saleh

Koumbi Saleh functioned as a principal urban center of medieval West Africa and is widely identified as the capital site of the Ghana Empire, a trading power active between the 9th and 13th centuries.

Location in present-day southeastern Mauritania, near the Malian border, placed the city along major corridors linking Saharan caravan routes with southern production zones.

Archaeological evidence points to occupation across many centuries, with peak urban activity occurring between the 11th and 14th centuries. Population density and scale of construction indicate one of the largest cities in West Africa during its period of prominence.

Trade, Wealth, and Political Authority

Economic strength relied on firm control of trans-Saharan exchange. Merchants crossed long distances carrying valuable materials, while royal authorities imposed taxes that reinforced centralized power and extended influence far outside the city itself.

Key commodities circulating through Koumbi Saleh included:

- Gold sourced in sub-Saharan regions

- Salt was transported northward by Berber caravans

- Imported luxury items are exchanged through long-distance commerce

Revenue derived from trade enabled rulers to maintain administrative systems, court structures, and military oversight.

Urban Structure and Social Organization

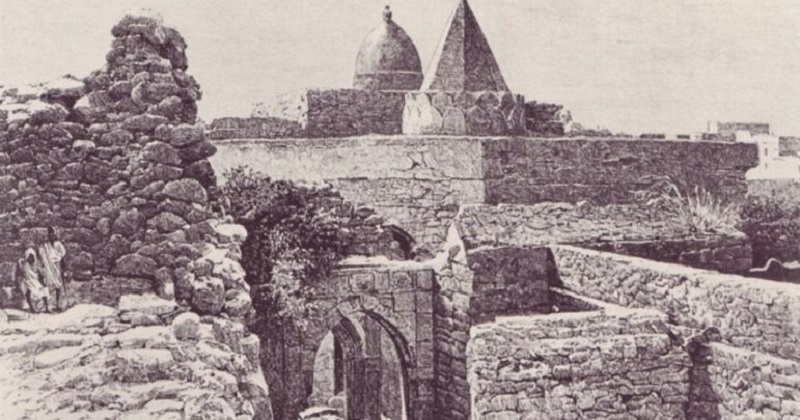

City layout reflected deliberate separation of functions tied to commerce and governance. Arabic geographers described Koumbi Saleh as two interconnected towns rather than a single compact settlement.

One section accommodated Muslim merchants and scholars, featuring mosques and stone-built residences. Another section served royal purposes, containing palace compounds, administrative buildings, and ceremonial spaces.

Continuous habitation across both areas produced a large, coordinated urban zone combining political authority, religious practice, and commercial activity.

Archaeological Evidence

Material remains reveal advanced construction techniques and extensive external connections. Findings recorded at the site include:

- Stone-built residential and commercial structures showing sustained building activity

- A congregational mosque used by Islamic communities

- Imported coins, ceramics, and glassware linked to North African exchange

Such evidence confirms Koumbi Saleh’s role as both a governing center and a commercial hub.

Decline and Abandonment

Shifts in trade routes and rising influence of neighboring powers weakened Koumbi Saleh’s position. Political disruption and conflict during the 12th and 13th centuries reduced its central role, leading to abandonment as an imperial capital.

Excavations conducted since the early 20th century have revealed foundations, street patterns, and material culture that allow reconstruction of the city’s former scale and importance.

4. Djado

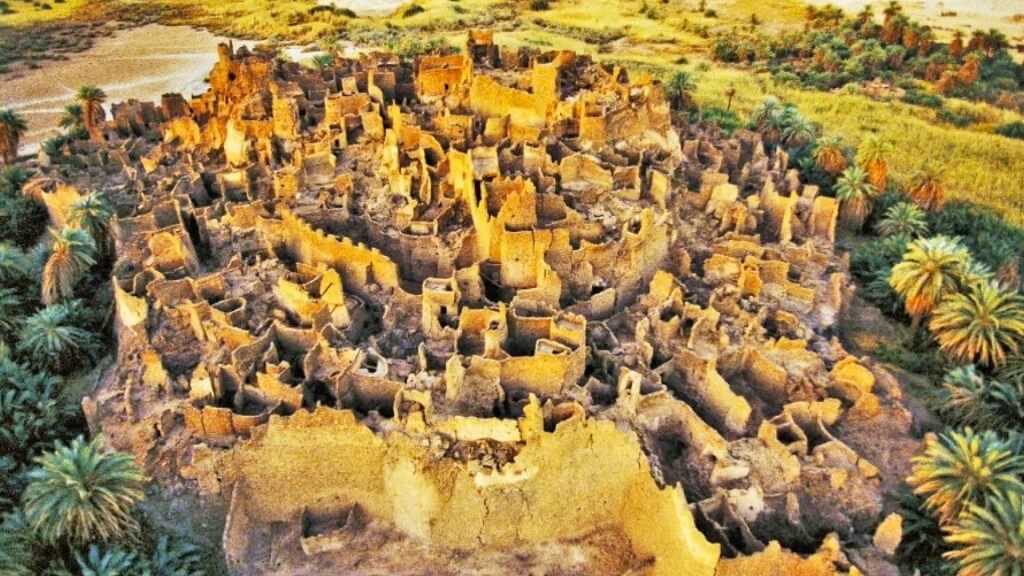

Djado refers to the ruins of an ancient settlement situated on a plateau in northeastern Niger. Position within the Ténéré region of the Sahara placed the site in one of the most demanding environments on the continent.

Despite harsh conditions, Djado developed as an oasis-based community capable of sustaining life and movement across desert terrain.

Centuries of habitation left behind striking ruins that rise above surrounding plains, marking a place shaped by adaptation and collective effort.

Political History and Regional Ties

Early settlement likely involved local populations such as the Sao people. During the medieval period, Djado entered the political sphere of the Kanem-Bornu state, especially under rulers like Dunama Dibalemi in the early 13th century.

Periods of autonomy alternated with reintegration under later leaders, including Idris Alauma during the 16th century.

Shifts in control reflected broader regional dynamics rather than isolation.

Economic Role and Trade

Strategic importance derived from access to underground water sources and protection offered by rocky escarpments. Oasis conditions enabled economic activity essential for desert travel.

Primary activities included:

- Date cultivation supported by subterranean water

- Salt production valued by caravan traders

Trade routes passing near the settlement linked interior West Africa with Saharan and North African networks, allowing Djado to function as a crossroads despite geographic isolation.

Architecture and Defensive Design

Physical remains offer insight into social organization and security concerns. Fortified villages, or ksars, were constructed of mudbrick and stone atop cliffs overlooking sandy expanses.

Visible architectural features include:

- Defensive walls enclosing elevated settlements

- Watch posts positioned for surveillance

- Clustered housing arranged for communal protection

Construction methods reflected adaptation to climate, terrain, and available materials.

Summary

Lost cities of West Africa reveal an urban and cultural past often excluded from global history.

Archaeological work paired with renewed respect for oral tradition continues to restore visibility to these societies.

Public education and further research remain essential for correcting narratives that long minimized African achievement.

Related Posts:

- 10 Lost African Kingdoms You’ve Probably Never Heard Of

- Top 10 Beach Destinations In Africa You Probably…

- 10 Interesting Facts About Ghana You Probably Didn’t Know

- Can You Drive Across Africa from West to East Safely?

- 12 Most Dangerous Animals in Africa (And Where You…

- 20 Dreamlike Places Around The World You Should…