Ashanti history unfolds through tales of conflict, sacred rites, and sharp political maneuvering.

Table of Contents

ToggleOnce part of a larger Akan collective, the Ashanti forged a separate identity through power struggles, spiritual symbolism, and tactical warfare.

Their empire rose on the strength of gold, unity, and relentless ambition—and fell only after decades of defiant resistance against British imperial forces.

What follows isn’t just a timeline. It’s the story of people who built something others couldn’t control.

Ashanti Origins and Dividing Legends

Ashanti oral traditions link their ancestry to a wider Akan collective once aligned with groups such as the Fante, Wassaw, and other Twi-speaking peoples.

Initial unity is seldom disputed, but the causes of eventual division spark contrasting narratives, each offering clues to cultural memory and self-definition.

These tales do more than explain separation—they reflect responses to pressure, shifts in power, and diverging values.

Some stories point to foreign interference as the root cause. In one widely shared legend, Fulani invaders swept across Akan territories, destroying vital food sources. The resulting famine forced the people to scour forests in search of sustenance.

- One group gathered fan, a local edible plant.

- Another relied on shan, another type of plant.

Both names later combined with “dti,” meaning “to eat,” forming Fan-dti and Shan-dti. Over time, those identifiers evolved into tribal markers, based on what was once a desperate act of survival, not heritage or bloodline.

Other versions shift the setting to royal courts, where tensions over loyalty and power triggered deeper fractures. In one account, the king faced a tribute conflict.

One group offered fan to express their loyalty. Another, discontented and subversive, sought to poison him using a deadly herb called asun.

- Fan-ti, denoting those who honored the throne.

- Asun-ti, branding those linked to rebellion and attempted regicide.

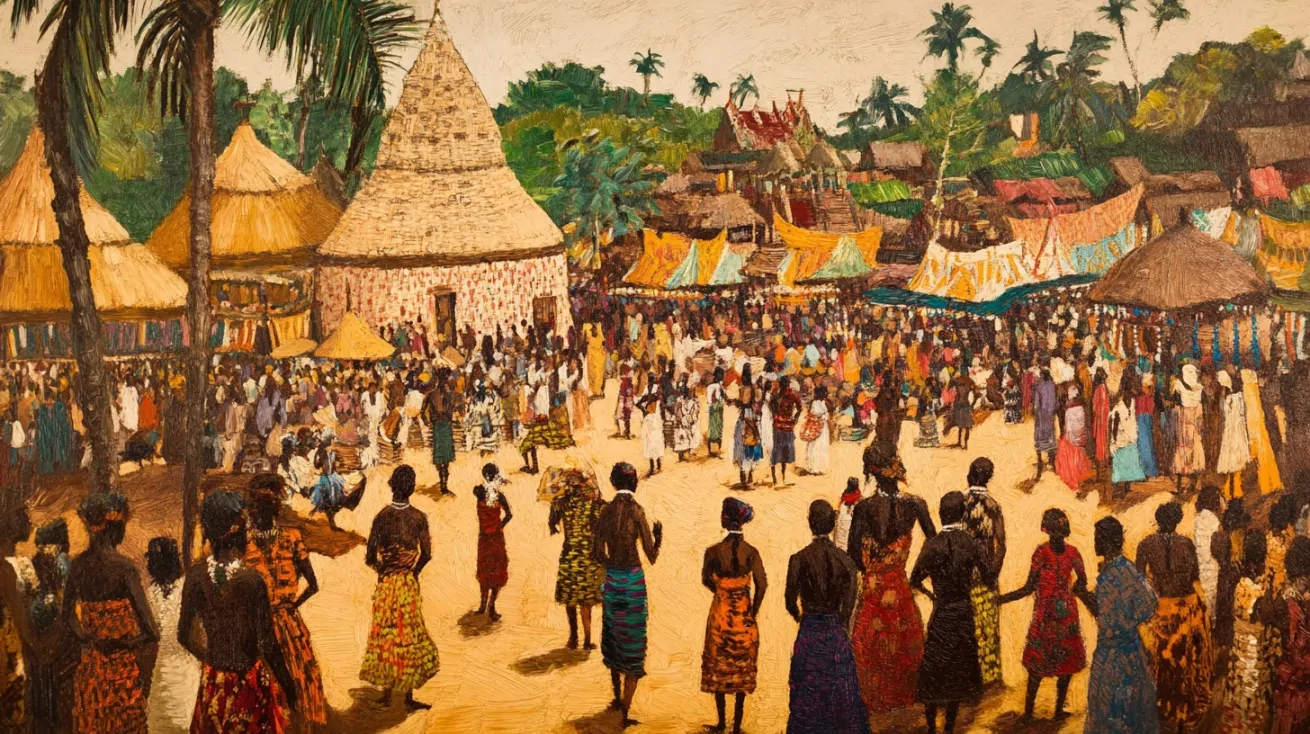

Westward Migration and the Rise of Trade Centers

Ancestors of the Akan peoples, including the Ashanti, are believed to have originated far to the east, in areas around Lake Chad and along the Benue River. Long migratory movements took these early groups westward, crossing major waterways like the lower Niger.

Passage through what is now Benin and Togo eventually brought them into the dense forests of southern Ghana, where the environment favored permanent settlement.

Resources shaped their future. Gold veins coursing through the soil and trees bearing kola nuts provided not only sustenance but also economic leverage. These commodities became the fuel for trade networks that spanned the region.

The ability to trade excess goods allowed communities to grow beyond subsistence, and with trade came structure, leadership, and strategic alliances.

By the 16th century, emerging settlements began to transition into organized states. Power centers formed as various Akan groups consolidated territories and economic influence. Among them were Bono in the north and several prominent southern states.

- Bono – Located further inland, known for early involvement in long-distance trade.

- Denkyira – Gained strength through control of gold production and external trade routes.

- Akwamu – Influential in the eastern corridor with military campaigns that reached toward present-day Accra.

- Fante – Occupied coastal zones and facilitated exchange with European merchants.

- Ashanti – Initially under Denkyira influence but rising steadily with control over inland trade paths.

Denkyira emerged as a dominant force during this period. Its access to gold sources and ability to coordinate large-scale trade gave it both wealth and power. Ashanti territory, although still forming, was gradually pulled into Denkyira’s orbit.

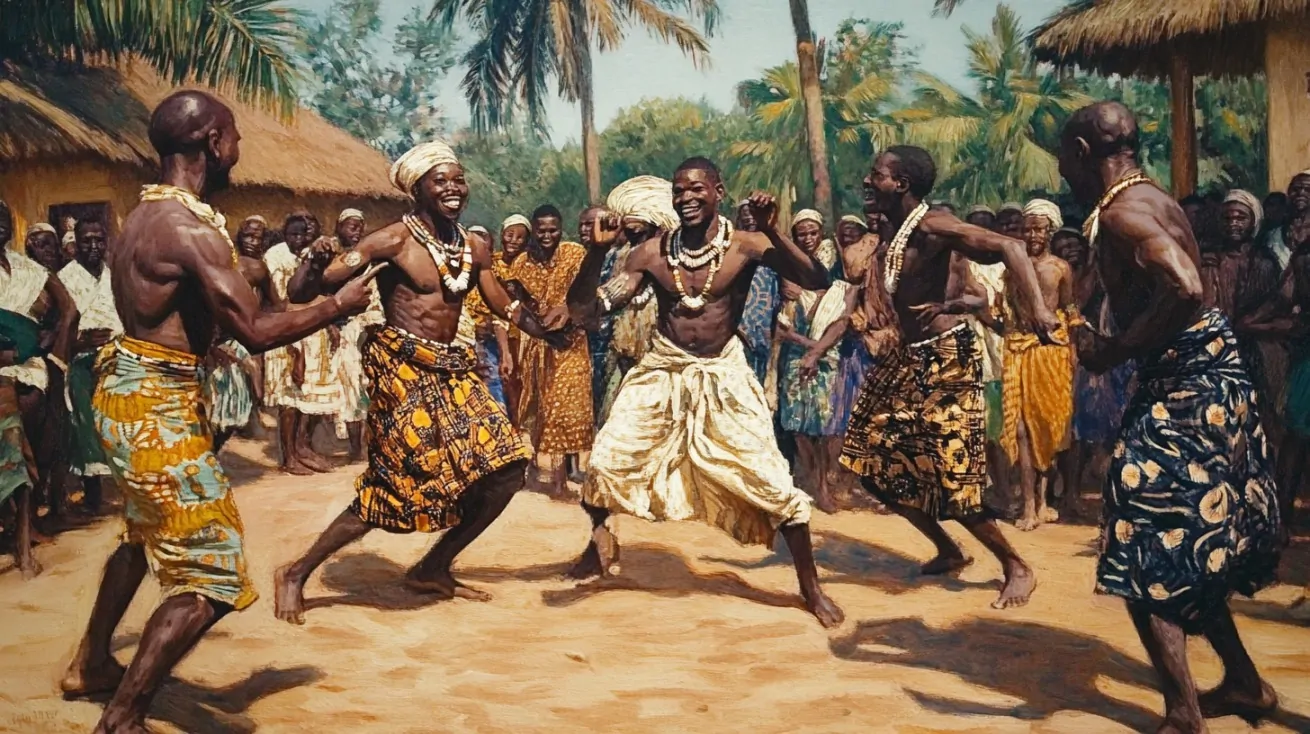

Strategic Unification and the Sacred Stool

Inland migration placed the Oyoko clan near Lake Bosomtwe, where fertile ground and intersecting trade routes created opportunity.

Kumasi, surrounded by gold-producing regions and kola nut groves, became a hub for movement and negotiation. Under Denkyiran dominance, the Oyoko operated with limited autonomy.

Yet Obiri Yeboa envisioned something greater—a collective identity, free from foreign control. His plans, ambitious though unrealized in his lifetime, set the foundation.

Osei Tutu, his nephew and successor, moved with both caution and boldness. Elevating his role above that of a typical clan leader, he assumed the title asantehene, or “king of the Ashanti.” That title, symbolic in its elevation, positioned him as more than a local ruler.

Okomfo Anokye, a priest of high reputation and Tutu’s trusted advisor, staged a spiritual event that sealed the deal. In front of clan leaders, he called forth a golden stool from the heavens.

No ordinary seat, this object represented more than authority. It carried the soul of the Ashanti people, anchoring their shared future in one visible symbol.

- Each clan head swore loyalty to the golden stool.

- The stool became the embodiment of collective identity and continuity.

- Internal rivalries softened in favor of a shared national structure.

Kumasi, strategically placed and symbolically chosen, emerged as the capital. Osei Tutu made it the seat of governance, embedding layers of authority within a newly formed council of clan heads. Political tradition took shape, not as imitation, but as evolution born of necessity. A formal constitution followed, codifying roles, rights, and responsibilities.

Expansion Under Royal Authority

Victory over Denkyira unlocked access to lucrative coastal exchange routes. Trade networks linked inland gold and kola regions to European merchants who sought captives and resources in exchange for textiles, firearms, and metal goods.

Control over such routes altered the trajectory of the Ashanti. Osei Tutu set the foundation, but his successor, Opoku Ware, constructed the framework of the empire.

Opoku Ware ascended during a period of internal consolidation. He leveraged memory and myth to unite factions still clinging to clan loyalties. One symbol held particular power—the Great Oath, “Koromante ne memeneda,” served as a spiritual and political tether.

Any pledge made in its name became absolute. No retraction followed once those words were spoken. Loyalty now bore both ceremonial weight and irreversible consequence.

Military campaigns under Opoku Ware expanded Ashanti territory.

- Sehwi: subdued early in Ware’s campaigns.

- Gyaman: a major acquisition along western borders.

- Akwamu: another powerful state brought under control.

- Akyem: defeated in 1742, granting Ashanti dominance over critical trade paths to the coast.

Power extended not only through conquest but through supply chains. Ashanti became dominant suppliers of captives, ivory, and gold. European merchants increasingly relied on them, as few others could guarantee consistent flows of goods.

Political structure shifted in tandem. Provincial chiefs lost grip as Opoku Ware installed loyalists who answered only to the throne. That change stirred unrest. Chiefs of Akyem and Wassaw, emboldened by prior autonomy, rebelled.

Their resistance failed to unravel the structure. By 1750, imperial cohesion remained intact. Opoku Ware had crafted an administration that could endure future pressures.

Tensions, Rebellions, and Fragile Peace

Kusi Obodum’s deposition in 1750 opened a contested path to succession. Osei Kwadwo emerged as ruler but faced a nation fragmented by growing rebellion. His rule demanded constant vigilance and calculated aggression. Twifo, Wassaw, and Akyem refused submission and rose in defiance.

Early in his reign, Osei Kwadwo allied with the Fante. Their support allowed initial suppression of rebel factions.

That cooperation deteriorated quickly, collapsing under mutual suspicion and competing goals. Without Fante support, Kwadwo pressed forward, unwilling to let the union fracture.

- Nobles of Ashanti blood were placed in charge of provinces, ensuring they reported only to the central authority.

- Coastal representatives were dispatched to forts and European outposts, enforcing rent payments and regulating transactions.

British merchants, growing in number and ambition, viewed such oversight as an obstacle. Smaller African states, exhausted by Ashanti levies and raids, saw Britain as a possible counterweight. As control extended toward the Atlantic, opposition gathered force. Another clash loomed on the horizon.

Clashes with British Forces

Conflict erupted in 1824. Ashanti forces—estimated at ten thousand—launched an offensive that overwhelmed a British-led coalition. Governor Charles MacCarthy fell in battle. His severed head, taken to Kumasi, marked a warning etched in blood.

Two years passed. British forces regrouped and returned, equipped with artillery and bolstered by reinforcements. At Kantamanto, Ashanti forces lost ground. The empire was forced to forfeit claims on coastal allies and tributary peoples, including the Akyem and Fante.

A pause followed, but pressure resumed in 1873 when Britain acquired Dutch forts, eliminating European competition along the coast. That shift triggered another invasion. Ashanti warriors, skilled in both ranged and close combat, could not match the firepower of British artillery.

Kumasi fell after fierce resistance. Ashanti leaders, once again, surrendered territory—this time all holdings south of the Pra River.

Attempts at resurgence continued. By 1895, another invasion unfolded. Britain targeted Kumasi again. Cannon blasts and sieges left Asantehene Agyeman Prempeh with little choice. To avoid full destruction of the capital, he surrendered and accepted exile. British flags replaced royal authority—but not the spirit of resistance.

Final Flames of Resistance

In 1901, resistance flared once more. Yaa Asantewa, the queen mother of Ejisu, emerged as the voice of defiance. Her leadership defied both colonial expectations and patriarchal convention. She rallied warriors, launched attacks, and revived the hope of independence.

Early gains painted her as a formidable tactician. Ashanti warriors, fighting on familiar ground, recaptured key points near Kumasi. British supply lines were strained under local pressure. But the empire struck back. Reinforcements arrived from Sierra Leone and Nigeria, bringing heavier weapons and larger battalions.

Ashanti forces were outgunned. Reports tell of Yaa Asantewa refusing surrender until defeat became absolute. She became the last commander to lay down arms. Ashanti power broke under British weight, and colonial rule took root. Gold Coast administration shifted entirely into British hands.

Ashanti sovereignty, once embodied in a stool descended from the sky, now lived only in stories, symbols, and memory.

Summary

Ashanti history tells of power forged through unity, sustained by military might, and tested through rebellion and war.

From sacred stools and trade gold to battle cries and colonial resistance, their legacy remains written in oral stories, royal symbols, and the enduring spirit of those who refused to kneel.

No surrender came easily. Even in defeat, echoes of resistance still speak.

Related Posts: