As a Mandika proverb reminds us, “the roof of a hut from one village will never fit a hut in a different village.” Language functions much the same way, it cannot be molded easily to fit frameworks foreign to its essence.

Table of Contents

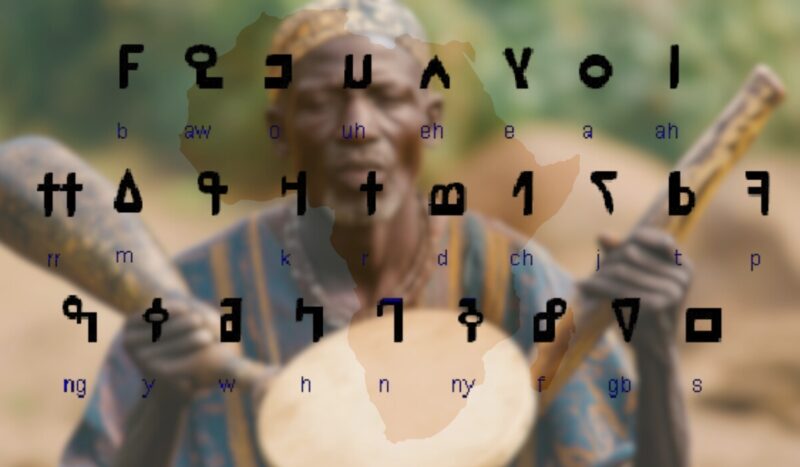

ToggleIn response to this linguistic mismatch, Souleymane Kanté introduced the N’Ko alphabet in 1949 to give Mande languages such as Mandika, Dyula, and Bambara a writing system crafted specifically for their phonetic structure.

A Script Created for the Sounds of a People

N’Ko alphabet was developed with a clear purpose — to address the limitations of foreign scripts in expressing the full range of phonological and tonal features found in Mande languages.

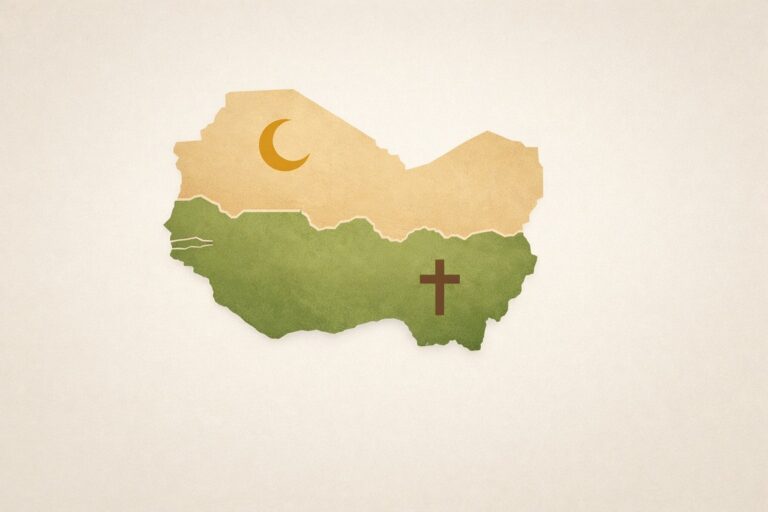

Arabic and Latin alphabets, while widespread due to colonial and religious influence, lacked the necessary tools to reflect the nuances of speech in languages such as Bambara, Mandika, and Dyula.

Without adequate symbols for vowel tones and pitch variations, written words became ambiguous, leading to misinterpretation and loss of meaning.

One syllable could carry drastically different meanings based on tonal inflection. For instance:

| Word | Possible Meanings |

|---|---|

| Da | Mouth, Door, A type of leaf |

| Su | Night, Corpse |

| Bala | Xylophone, Porcupine |

Such tonal distinctions play a central role in communication. Foreign alphabets simply did not account for these subtleties, making it nearly impossible to faithfully transcribe spoken language into written form.

Souleymane Kanté’s approach was rooted in collaboration and observation. Rather than impose an external standard, he engaged directly with local communities.

Illiterate villagers were invited to participate in a simple but insightful experiment, to draw symbols or letters in a way that felt natural and instinctive.

Through this process, Kanté discovered a clear pattern: most participants began writing right to left.

He honored this tendency, aligning the direction of the script with the people’s intuitive flow.

As a result, N’Ko alphabet became more than a technical solution. It took shape as a living extension of cultural rhythm and oral tradition.

- Directionality: Right-to-left orientation based on community preference.

- Phonological precision: Symbols tailored to tonal language, including vowel tones and nasalization.

- Alphabet structure: A true alphabet rather than a syllabary, allowing more flexibility and precision.

- Cultural resonance: Letterforms shaped by local intuition, not imported frameworks.

Structure and Functionality of the Script

N’Ko functions as an alphabet, not a syllabary, allowing for precise phonetic representation and greater adaptability when integrating foreign vocabulary.

Each character corresponds to a distinct sound, making the script both logical and efficient for writing native Mande languages.

Seven vowel characters form the foundation of the phonetic system.

- ߊ: /a/ as in “Africa”

- ߋ: /e/ as in “Lomé”

- ߌ: /i/ as in “Mali”

- ߍ: /ɛ/ as in “Senegal”

- ߎ: /u/ as in “Timbuktu”

- ߏ: /o/ as in “Togo”

- ߐ: /ɔ/ as in “Mosque”

Tonal precision is essential. Short and long tones, marked by diacritics, give shape to meaning. A change in pitch can shift a word’s definition completely. In addition to tone, nasalization marks offer further clarity in pronunciation.

Tone variations include:

| Tone Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Short high tone | Elevated pitch |

| Short low tone | Dropped pitch |

| Short rising tone | Begins low, rises to neutral |

| Long high tone | Lengthened vowel, consistently high |

| Long low tone | Lengthened vowel, consistently low |

| Long rising tone | Gradual pitch increase over a long vowel |

| Long descending tone | Falls in pitch across a long vowel |

| Nasalization | Adds a nasal quality to the vowel |

Consonants number 19, complemented by one nasal syllabic letter (ߒ) and two abstract forms used under specific phonetic conditions.

Punctuation, Numbers, and Orthographic Flexibility

Punctuation in N’Ko mirrors several elements familiar to Latin script users, yet introduces distinct forms that are deeply tied to its design.

Marks like the period (.), comma (߸), colon (:), and parentheses ( ) remain recognizable, while others like the question mark (⸮), exclamation point (߹), and asterism (߷) reflect localized evolution.

Numbers in N’Ko follow a logical structure, ranging from ߀ (0) to ߉ (9). Arranged from right to left, numerals reflect the same directionality as the script itself. To indicate ordinals like “1st” or “3rd,” a tonal or nasal diacritic is applied to the numeral.

Efficiency in writing is achieved through practical vowel omission rules.

- If two different consonants are followed by the same vowel with the same tone, the first vowel is omitted.

- If both consonants and vowels are identical in sequence, all vowels remain.

- In longer words, when the same vowel appears more than twice with the same tone, only the first instance may be dropped, while the remaining two are retained.

Apostrophes perform dual grammatical functions:

- Replace a vowel at the end of a word when the following word begins with a vowel.

- Mark the absence of vowel sounds in foreign-origin words, especially in consonant-heavy sequences, preventing misinterpretation.

Adapting to Global Influence

Adaptability lies at the heart of N’Ko’s strength. Instead of being restricted to native phonology, N’Ko alphabet modifies existing characters to represent non-Mande sounds.

Key modifications are achieved using diacritic marks. Two dots above a vowel adjust it toward foreign pronunciations such as the French “u” (ߎ߳) or “e” (ߋ߳).

A tone mark on the letter “fa” (ߝ߭) transforms it into “va.”

The consonant “ja” (ߖ) can be altered to:

| Original Sound | Modified Form | Resulting Sound | N’Ko Character |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ja (ߖ) | Tone mark | z | ߖ߭ |

| Ja (ߖ) | Two dots | zh | ߖ߳ |

| Ra (ߙ) | Tone mark | French hard r | ߙ߭ |

| Gba (ߜ) | Tone mark | g | ߜ߭ |

| Gba (ߜ) | High tone | gh | ߜ߫ |

| Gba (ߜ) | Two dots | kp | ߜ߳ |

| Sa (ߛ) | Tone mark | sh | ߛ߭ |

| Sa (ߛ) | High tone | sch | ߛ߫ |

| Ta (ߕ) | Tone mark | th (English) | ߕ߭ |

| Cha (ߗ) | Tone mark | Soft j | ߗ߭ |

Even complex names such as “Christophe” are rendered as ߞߑߙߌߛߑߕߐߝ, read as “K’ris’tof,” preserving original pronunciation through strategic diacritic use.

Enduring Legacy and Global Presence

No West African government has formally adopted N’Ko alphabet, yet the script thrives. Through handwritten texts, personal teaching, and widespread transcription, Kanté seeded a literacy movement.

Works include religious, scientific, historical, and philosophical texts, many of which continue to circulate in local schools and cultural institutions.

Universities in countries like the US, Spain, and Egypt teach N’Ko alphabet. Newspapers, public health brochures, and educational material regularly feature the script. Organizations such as the Red Cross use it to engage local communities effectively.

In 2006, N’Ko entered the Unicode Standard. Technological integration followed with digital fonts, smartphone keyboards, and language apps — expanding its accessibility to new generations.

N’Ko survival and growth represent more than functional literacy. It affirms identity, roots language in cultural reality, and invites a future where African voices define their own written expression.

Related Posts: