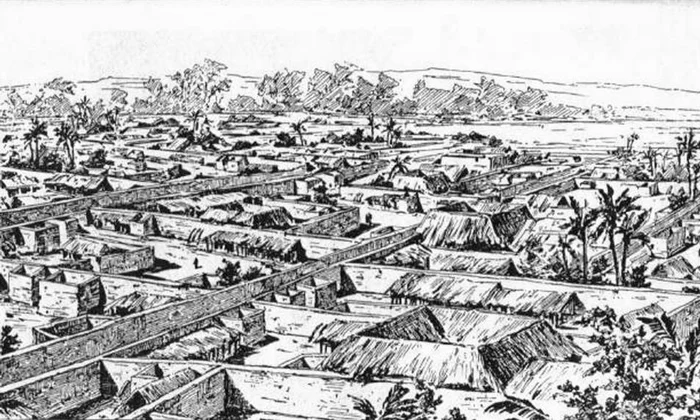

Yoruba people form one of the largest ethnic groups in Nigeria, concentrated in the southwestern region and present in parts of North Central Nigeria and the Republic of Benin.

Table of Contents

TogglePopulation estimates place them in the tens of millions.

Social organization historically centers on towns, lineages, and royal institutions led by obas.

Religious thought recognizes a supreme being along with divinities known as orisa, ancestors, and spiritual forces that influence daily life.

- Art

- Color

- Animal imagery

Protective marks and spiritual symbols operate as social identifiers, sacred protections, and communicative tools within communal life.

Body markings such as ila function alongside color codes and animal representations to transmit values, structure identity, and guard against spiritual danger.

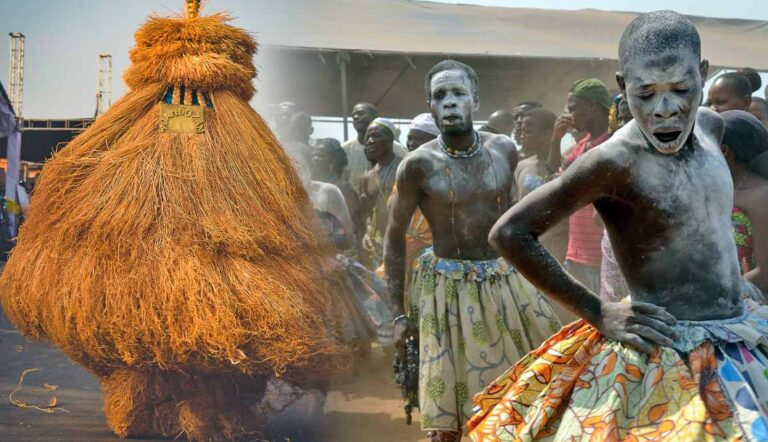

Protective Marks – Tribal Marks and Scarification

Tribal marks known as ila consist of permanent incisions made on the cheeks or other parts of the body, usually during infancy or early childhood.

Skilled practitioners used sharp instruments to cut the skin, sometimes applying charcoal or herbal substances to ensure visibility and healing.

| Patterns Varied By |

|---|

| Town |

| Clan |

| Lineage |

Design structure communicated ancestry at a glance. Some consisted of three or more vertical lines carved into each cheek. Others displayed horizontal strokes or diagonal slashes.

- Abaja, often composed of multiple vertical lines

- Keke or Gombo, characterized by shorter grouped cuts

- Pele, associated with particular towns and linear formations

Scarification extended marking practice to chest, arms, and abdomen. Tattoo, in certain communities, accompanied scarification as another form of bodily inscription.

Design intention differed depending on the purpose. Some patterns were ornamental and reinforced ideals of beauty.

Others carried ritual weight tied to protection or healing. Pain endured during incision symbolized courage, endurance, and readiness to participate in communal life.

Cultural and Social Functions

Identity and lineage formed the primary foundations of facial marking. Visible scars eliminated ambiguity concerning origin and kinship.

Immediate recognition supported social cohesion in complex urban centers and in periods of political instability.

During war, forced migration, or enslavement, marked individuals could be traced to their families. Physical signs reduced anonymity and reinforced kin networks.

Standards of beauty influenced the adoption and continuation of marking practice. Facial symmetry and clarity of incision signified aesthetic refinement.

Cultural ideals valued resilience displayed through the willingness to endure cutting. Marks thus communicated both ancestry and personal strength.

Social hierarchy also appeared through design. Certain lineages maintained distinctive patterns reserved for royal or noble families.

Royal households guarded these patterns as insignia of authority. Installation rites for some obas included scarification as part of the enthronement ritual.

Such acts communicated readiness to assume sacred responsibility and to exercise political authority under divine sanction.

Protective intention remained a major motive in many communities. Beliefs concerning abiku shaped decisions about marking infants.

Abiku referred to children believed to die repeatedly and return to cause grief. Scarification applied to such children aimed to disrupt recurring death cycles and to mark them visibly within spiritual perception.

Spiritual Significance

Spiritual meaning attached to scarification rested on the belief that body and spirit remain interconnected.

Blood released during incision carried symbolic weight. Drawing blood could represent agreement with ancestral forces or deities acknowledged by the lineage.

Some families believed marked skin strengthened spiritual identity and secured divine favor.

Ritual specialists sometimes directed specific incisions as part of initiation or healing.

Placement of cuts, number of strokes, and timing of ritual action held sacred significance. The body, therefore, became a site of sacred inscription.

Physical alteration conveyed metaphysical meaning, tying individual identity to ancestral continuity and divine oversight.

Role in Ritual and Leadership

Leadership structures integrated bodily symbolism into governance.

Royal enthronement ceremonies in certain Yoruba polities included ritual cuts administered to the incoming ruler.

Scarification in this context expressed readiness to carry the spiritual burden associated with kingship.

Authority in Yoruba political thought requires more than administrative capacity. Sacred legitimacy rests on visible signs linking the ruler to ancestral and divine sanction.

Marked bodies communicated continuity within dynastic succession. Scar patterns could indicate rightful membership in ruling houses. Public visibility of such marks reinforced communal trust in leadership.

Modern Transition

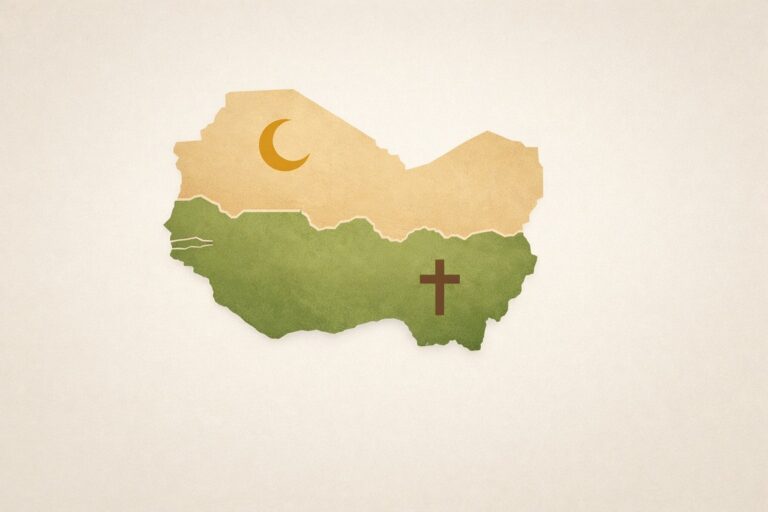

Colonial administration, expansion of Christianity and Islam, and postcolonial state regulations contributed to the decline in facial scarification.

Medical concerns regarding infection and consent influenced social attitudes. Formal identification systems reduced reliance on visible lineage markers.

Urban life reshaped aesthetic standards. Many families chose not to mark children due to social stigma or professional disadvantage.

Legal frameworks in contemporary Nigeria discourage permanent marking of minors.

Adaptation continues in new forms. Tattoo culture has adopted traditional motifs in modified styles. In urban centers, some individuals who later reconsider permanent body art seek professional laser tattoo removal as part of changing personal or social priorities.

Younger generations sometimes choose symbolic designs referencing ancestral patterns without replicating older facial scars.

Identity and protective memory remain embedded in collective consciousness even as widespread scarification decreases.

Spiritual Symbols in Yoruba Culture

@scienceinyoruba Names of these symbols in Yoruba: ^, ∧, ∨#masoyinbo #yoruba #scienceinyoruba ♬ original sound – Science in Yoruba

Symbolic language extends beyond bodily inscription into color, animal imagery, and artistic production.

Visual codes communicate moral and theological meaning within ritual life and social interaction.

Color functions as a structured system of sacred communication.

- White, known as funfun, signifies purity, sacred presence, and moral clarity

- Red, or pupa, conveys vitality, courage, and concentrated spiritual force

- Black, or dudu, relates to ancestral depth, hidden power, and mystery

- Blue suggests calmness, harmony, and spiritual balance

Ritual clothing and shrine decoration follow these codes. Devotees of certain orisa wear prescribed colors during ceremonies.

Arrangement of hues in festival attire transmits layered meaning without spoken explanation.

Animal Symbolism

Animal imagery occupies a central place in Yoruba thought and oral literature.

Symbolic associations link particular animals with political authority and moral attributes.

- Eagle, Asa, representing authority, elevated vision, and protective oversight

- Leopard, Amotekun, signifying strength, royal power, and fearlessness

- Elephant, Erin, symbolizing wisdom, longevity, and social stability

- Python, associated with regeneration and cyclical continuity

Royal regalia often incorporates leopard skins to assert dominance. Praise poetry compares respected leaders to elephants, signaling weight and influence. Proverbs employ animal metaphors to instruct listeners in ethical conduct.

Use in Rituals and Art

Artistic production encodes spiritual knowledge through recurring motifs. Patterned cloth displays proverbs and communal memory in visual form.

Carved doors and shrine figures present iconography tied to specific orisa and ancestral narratives.

Ritual paraphernalia integrate color and animal imagery to organize sacred space.

Participants recognize symbolic arrangements and respond according to established custom.

Visual culture thus functions as a communicative system reinforcing social order and spiritual belief.

Intersection of Protective Marks and Spiritual Symbolism

Protective marks and symbolic imagery operate within a shared network of meaning.

Body inscriptions correspond with motifs found in cloth, sculpture, and ritual objects.

Facial incisions intended to guard against abiku, parallel use of white garments for purification or leopard imagery for strength.

Protection occurs at personal and communal levels. Scarification addresses bodily vulnerability.

Color codes and animal symbols reinforce collective security and moral stability. Repetition of these signs across generations sustains cultural continuity.

Collective memory depends on embodied and artistic transmission. Marks on skin, animals in proverbs, and ritual colors form an integrated system shaping identity and belief.

Case Studies and Examples

Distinct marking styles reveal geographic and familial affiliation. Abaja marks often consist of several vertical lines carved into each cheek.

Keke or Gombo patterns include shorter, grouped incisions. Pele marks display linear formations associated with specific towns.

Historical records describethe identification of displaced individuals through facial scars.

Royal families maintained exclusive designs signaling noble origin. Ritual application varied according to context.

Children identified as abiku received protective cuts intended to secure survival.

Prospective rulers underwent scarification linked to enthronement. Healing rites sometimes prescribed incisions accompanied by herbal treatment and spoken incantation.

Animal symbolism appears prominently in royal courts. Leopard skins signal authority. Elephant imagery conveys dignity and endurance.

White garments dominate ceremonies dedicated to divinities associated with purity. Red adornments mark rites connected to forceful spiritual power.

Contemporary Perspectives and Challenges

Modern Nigerian society subjects scarification to legal and medical scrutiny.

Urban families frequently reject facial marking due to stigma and changing professional norms. State policies discourage permanent marking of minors.

Cultural revival movements reinterpret traditional symbols in painting, fashion, and contemporary tattoo practice.

Tattoos inspired by Yoruba motifs allow individuals to assert heritage without undergoing childhood scarification.

Religious communities maintain color symbolism and animal imagery within ritual life.

Devotees of traditional religion continue to observe prescribed visual codes linked to particular orisa.

Diaspora communities in the Americas and Europe adopt similar systems during festivals and worship.

Adaptation allows continuity. Visible facial marks may decline in prevalence, yet symbolic language rooted in color, animal imagery, and sacred inscription remains active in communal life.

The Bottom Line

Protective marks and spiritual symbols occupy central positions in Yoruba social and religious organization.

Tribal marks historically defined lineage, signaled beauty and status, and functioned as spiritual safeguards, including protection against abiku and other perceived threats.

Color codes and animal imagery communicate moral, political, and theological concepts within ritual and artistic contexts.

Yoruba cultural expression demonstrates how bodily marks and symbolic imagery construct identity, regulate social order, and articulate sacred meaning within a complex society.

Related Posts:

- English vs. Yoruba Intellectual Production -…

- Meaning of Sharing a Calabash - Food as Communal…

- Dream Interpretation in West African Spiritual Practices

- 25 Fascinating Facts About the Yoruba Tribe You Didn’t Know

- What Was the Role of Women in Pre-Colonial West…

- What Is It Like to Date an African Woman? Top…