Africa has long shaped human progress through innovation in science, technology, and social organization.

Table of Contents

ToggleWest Africa played a central role in this process, producing systems and tools that influenced agriculture, trade, governance, and daily life across wide regions.

Societies developed practical solutions rooted in observation, experimentation, and collective knowledge, allowing complex communities to flourish over centuries.

Seven ancient West African inventions reveal how early thinkers addressed challenges tied to:

- Food production

- Resource management

- Communication

- Construction

- Timekeeping

Advances in mathematics, ironworking, navigation, writing, and engineering supported economic growth and political stability while shaping ideas that later spread across continents.

1. Early Mathematics and Numerical Systems

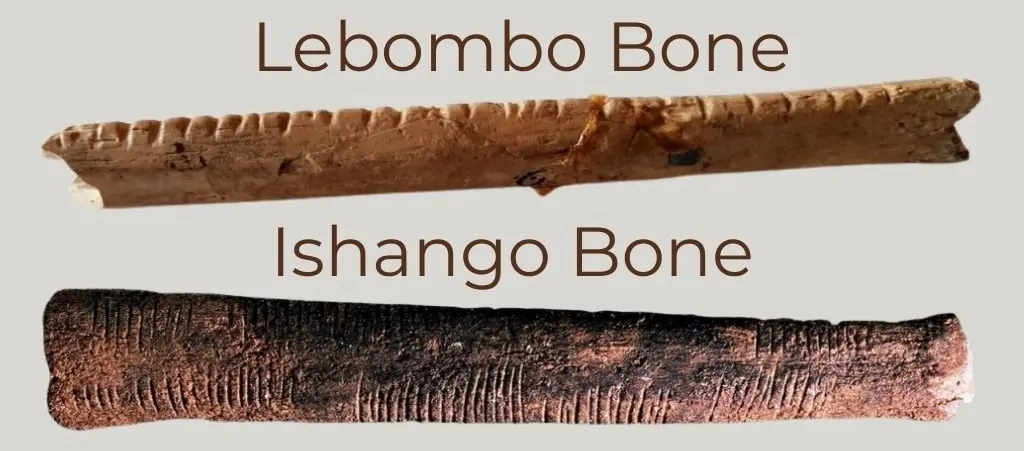

Early mathematical thinking appeared in Africa at an exceptionally early point in human history, shaping how communities measured time, quantity, and resources tied to survival and social coordination.

Physical evidence confirms deliberate numerical reasoning long before formal writing systems took shape.

Objects uncovered by archaeologists point to structured thought connected to planning, observation, and repetition rather than decorative or random marking.

Material evidence shows how numerical logic operated in everyday contexts and abstract reasoning.

Key artifacts clarify these early practices:

- Lebombo Bone in Southern Africa, dated over 40,000 years old, contains a sequence of carved notches likely used to track lunar cycles, inventories, or seasonal change

- Ishango Bone in Central Africa displays grouped markings that suggest arithmetic relationships, doubling patterns, and base ten counting

Numerical reasoning supported recordkeeping for trade agreements, labor coordination, and agricultural planning. Quantitative thinking allowed communities to regulate food distribution, predict seasonal shifts, and align collective activity.

Mathematical literacy strengthened economic exchange and supported early scientific observation connected to astronomy and time measurement across African societies.

2. Iron Metallurgy and Blacksmithing

Iron metallurgy reshaped daily life and political authority across West Africa through independent technological development rooted in experimentation and environmental knowledge.

Nok culture, located in present-day Nigeria around 1000 BCE, represents one of the earliest iron smelting societies in sub-Saharan Africa.

Archaeological remains reveal furnaces, slag deposits, and forged tools that point to advanced technical skill without reliance on outside transfer.

Iron production affected multiple aspects of society in concrete and lasting ways:

- Agricultural tools such as hoes and plows increased food output and land use

- Weapons strengthened defense and altered warfare practices

- Blacksmiths gained elevated social status, often holding sacred or elite roles due to control over fire and metal

Trade networks expanded as iron tools circulated across wide regions. Routes associated with the Ghana Empire connected local markets and supported trans Saharan exchange, reinforcing political organization, military strength, and economic stability.

3. Agricultural Domestication and Crop Innovations

Agricultural innovation supported population growth and the rise of complex societies across West Africa through deliberate environmental management.

Crop domestication allowed communities to control food production rather than rely solely on hunting and gathering.

Yam domestication ranks among the earliest known examples of managed agriculture and became central to daily diets, ritual practice, and local economies.

Food security depended on crops adapted to regional conditions and climate patterns. Two examples shaped long-term stability:

- Yams provided reliable calories and social value tied to harvest rituals

- Sorghum offered a drought-resistant cereal suited to variable rainfall

Sustained food production encouraged permanent settlements and supported the formation of states such as Mali and Songhai. Agricultural knowledge later spread internationally, shaping diets and farming systems across Asia and the Americas.

4. Navigation and Watercraft

River systems functioned as vital channels for trade, communication, and cultural exchange across West Africa.

Dugout canoes carved out of hollowed tree trunks allowed efficient travel along major waterways such as the Niger River.

Movement of goods and people strengthened social ties among inland communities separated by long distances.

River-based commerce supported economic growth through several interconnected activities:

- Transport of agricultural goods, iron tools, and raw materials

- Exchange of ideas, language, and cultural practices

Urban centers such as Timbuktu flourished through access to waterborne trade routes. Watercraft technology enabled regional integration across floodplains and river networks that linked distant settlements into shared economic systems.

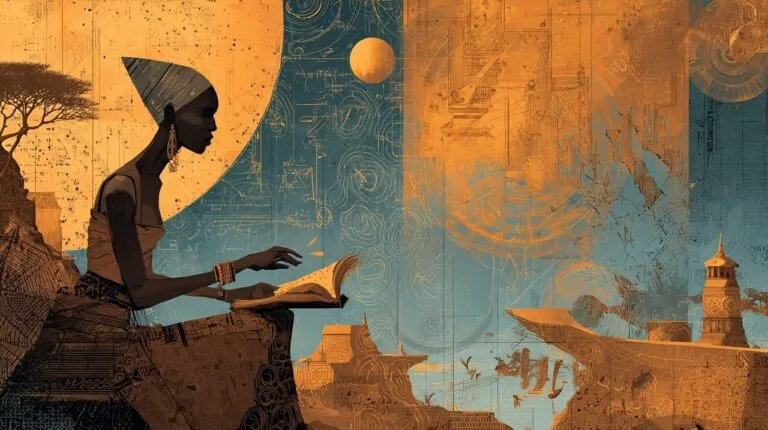

5. Written Communication and Recordkeeping

Written communication existed in West Africa prior to European contact through indigenous systems of symbolism and documentation tied to governance and belief systems.

Nsibidi script, developed in the Cross River region, functioned as an ideographic system used for law, social regulation, and spiritual expression.

Symbols conveyed meaning visually rather than phonetically.

Use of Nsibidi extended into organized social structures that relied on controlled knowledge:

- Ekpe societies employed symbols to enforce laws and regulate behavior

- Visual communication transmitted complex ideas across communities without spoken language

Written systems operated alongside oral traditions and reflected advanced bureaucratic organization. Papyrus traditions associated with Egypt contributed to broader African practices of documentation that influenced later recordkeeping systems elsewhere.

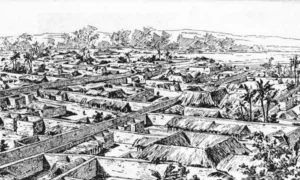

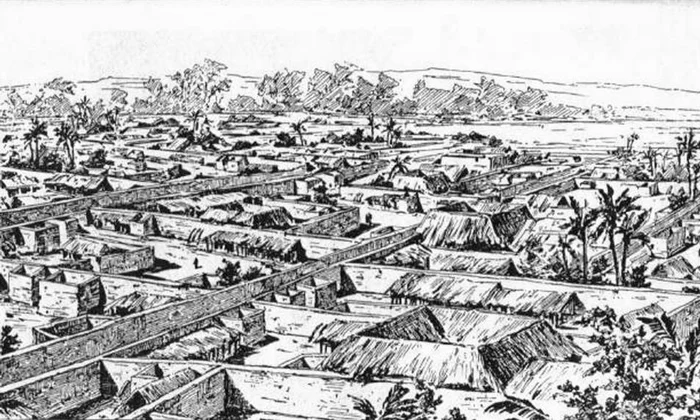

6. Architectural and Engineering Innovations

Urban planning and engineering advanced significantly in ancient West Africa through long-term settlement, experimentation, and adaptation to environmental conditions. Djenné Djenno in Mali ranks among Africa’s oldest known urban centers, with continuous occupation dating to 250 BCE.

Archaeological work shows intentional city organization rather than unplanned growth. Streets, residential zones, and public areas followed consistent patterns that supported trade, governance, and daily life.

Excavations reveal durable housing foundations, compact neighborhoods, and drainage systems designed to manage seasonal flooding along the Niger River basin. Engineering solutions addressed climate challenges while supporting dense populations over centuries.

Construction reflected shared knowledge passed across generations through skilled labor and apprenticeship.

Building practices relied on materials readily available in the surrounding environment, shaped through refined technique and communal effort. Structural features demonstrate both practicality and symbolism:

- Mudbrick walls engineered to support multi story buildings and regulate indoor temperature

- Decorative facades used to signal social rank, communal identity, and religious meaning

Architectural methods reached clear expression in monumental structures such as the Grand Mosque of Djenné. Annual replastering rituals reinforced community participation and preserved technical knowledge.

Construction techniques and urban planning principles influenced Saharan and Sahelian cities across broad areas, supporting trade hubs, administrative centers, and religious institutions.

7. Mathematical Calendars and Timekeeping

Astronomical observation played a central role in organizing social and agricultural life through careful attention to recurring celestial patterns. Communities tracked movement of the sun, moon, and stars to predict seasonal change and coordinate collective activity.

Observation required precise counting, pattern recognition, and long-term recordkeeping passed across generations.

Timekeeping shaped multiple aspects of society by regulating labor, ritual, and governance. Calendar systems coordinated activity through repeated cycles tied to environmental rhythm:

- Alignment of farming schedules with solar and lunar movement to maximize crop yield

- Timing of rituals, ceremonies, and leadership transitions connected to celestial events

Agricultural success depended on accurate timing of planting and harvest periods. Mathematical and astronomical knowledge guided decision-making in everyday life, reinforcing social stability and resource management across West African societies.

The Bottom Line

Seven ancient West African inventions reveal how innovation shaped society through practical knowledge and scientific reasoning.

Developments in mathematics, iron metallurgy, agriculture, navigation, writing systems, architecture, and timekeeping supported population growth, trade networks, and political organization across wide regions.

RIdeas developed in West Africa influenced food systems, construction methods, economic exchange, and scientific thought across continents. Accurate representation of these contributions strengthens historical narratives and affirms Africa’s central role in shaping the modern world.

Related Posts: