The Fulani, also known as Fula or Peul, are one of the largest and most widely dispersed ethnic groups in Africa, numbering over 40 million people across more than 20 countries.

Table of Contents

ToggleTheir presence stretches from Senegal and Mauritania in the west to Sudan and the Central African Republic in the east, forming a cultural thread that connects West and Central Africa.

What makes the Fulani remarkable is not just their size or mobility, but their deep sense of identity, defined by pastoral life, Islamic scholarship, and a strict moral code called pulaaku, which governs dignity, patience, and self-control.

This combination of mobility, discipline, and adaptability has allowed the Fulani to thrive across centuries, surviving colonial disruptions, droughts, and modern borders, while maintaining one of Africa’s most distinctive and enduring cultural systems.

Origins and Early History

The origins of the Fulani are complex and debated. Linguistically, they belong to the Atlantic branch of the Niger-Congo family, and their early movement likely began around the Senegambian region more than a thousand years ago.

Over centuries, they migrated eastward in waves, herding cattle, trading, and spreading Islam.

By the 11th century, Fulani communities were already established in Futa Toro (modern Senegal), Futa Jallon (Guinea), and Macina (Mali). Their expansion coincided with the rise of major Islamic centers like Timbuktu and Gao, where Fulani scholars contributed to the transmission of Arabic learning and Quranic education.

The Fulani Jihads and Political Influence

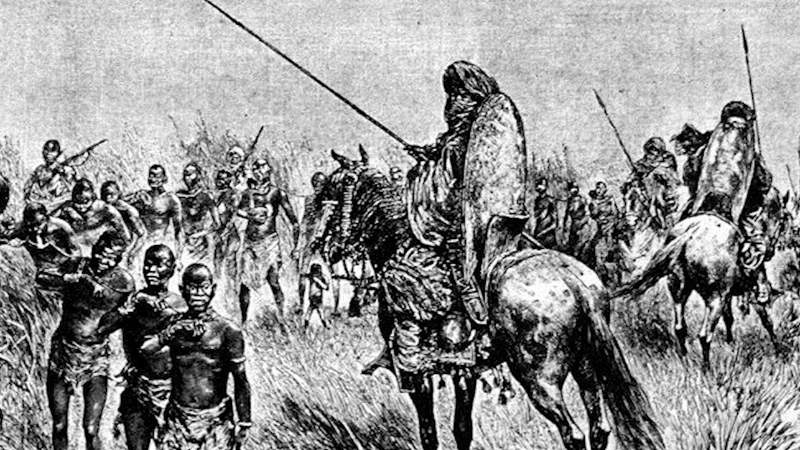

Between the 18th and 19th centuries, the Fulani played a decisive role in West African history through a series of Islamic reform movements known as the Fulani Jihads. These movements aimed to purify Islam and establish theocratic governance.

The most famous of these was led by Usman dan Fodio, who founded the Sokoto Caliphate in 1804, one of the largest pre-colonial empires in Africa. At its peak, Sokoto ruled over parts of modern Nigeria, Niger, and Cameroon, uniting diverse peoples under Islamic law and Fulani leadership.

Other Fulani-led states included:

| State | Founder | Modern Region | Historical Significance |

| Futa Toro | Suleiman Baal | Senegal | First Fulani Islamic theocracy (1770s) |

| Futa Jallon | Karamoko Alfa | Guinea | Hub of Islamic scholarship |

| Sokoto Caliphate | Usman dan Fodio | Nigeria | Most powerful Fulani state |

| Massina Empire | Seku Amadu | Mali | Theocratic rule along the Niger River |

These states shaped the political and religious map of West Africa and set lasting foundations for Islamic learning that continue today.

Culture and Social Structure

Fulani society is built around pulaaku, a code of conduct emphasizing modesty (semteende), patience (munyal), courage (ngorgu), and wisdom (hakkiilo).

This moral system shapes everything from how one speaks to how one handles conflict.

Socially, Fulani communities are traditionally hierarchical but flexible:

| Social Class | Role |

| Fulɓe Na’i (Pastoral Fulani) | Cattle herders, nomadic families |

| Town Fulani (Fulɓe Wuro) | Settled communities, traders, scholars |

| Rimɓe | Artisans, farmers, and lower-status groups |

| Slaves (Maccube) | Historically captured in wars, later integrated into society |

While social distinctions existed, Islamic brotherhood and the shared identity of being Pullo (a Fulani person) often bridged divisions, especially in spiritual and communal life.

Language and Identity

The Fulani speak Pulaar or Fulfulde, a tonal language with dozens of dialects that stretch across Africa. Hausa remains the most widely spoken language in West Africa, yet Fulfulde holds a unique role as a bridge among nomadic and settled communities.

Despite regional differences, mutual understanding remains strong, a testament to their wide network of mobility and trade.

Language is a marker of pulaaku: correct speech, calm tone, and poetic expression are signs of nobility. Proverbs play a key role in communication. One common saying is:

“Munyal deefan hayre”, Patience can cook a stone.

Religion and Spiritual Life

The Fulani are predominantly Muslim, and Islam has been central to their identity for over a millennium. Fulani scholars were among the earliest to translate and teach Quranic knowledge in local languages, and many families maintain private Islamic schools (madrasas).

However, pre-Islamic spiritual traditions also survive in subtle forms, such as belief in ancestral spirits (jenun), protective charms, and rituals around fertility, cattle health, and rain. These practices coexist with Islam in a form of syncretic faith, especially among rural Fulani.

Pastoral Life and Economy

For many Fulani, cattle are life. Herds are not just economic assets but symbols of prestige, love, and lineage continuity.

The nomadic Fulani follow seasonal routes across savannahs and Sahel regions, moving between dry and wet season pastures.

| Aspect | Description |

| Main Livestock | Cattle (zebu), goats, sheep |

| Trade Goods | Milk, hides, cheese, butter |

| Mobility Pattern | Transhumance – seasonal migration |

| Environmental Role | Fertilization of fields, seed dispersal |

| Modern Challenges | Drought, desertification, and land conflicts |

In settled areas, many Fulani have turned to farming, commerce, and education, yet the symbolic power of the herds remains strong in collective memory and art.

Art, Dress, and Beauty

Fulani art emphasizes elegance and restraint. Women are known for elaborate hairstyles, gold jewelry, and tattooing, especially around the lips and gums, signifying beauty and maturity.

Men often wear embroidered robes (boubous) and carry finely crafted leather accessories. The calabash, used to store milk, is often intricately engraved and passed down through generations.

Fulani music features one-string fiddles (hoddu), flutes, and chants that blend Islamic poetry with pastoral themes. The rhythm often mimics the pace of walking herds, slow, steady, and contemplative.

Festivals and Marriage Customs

A highlight of Fulani culture is the Gerewol Festival, celebrated by the Wodaabe subgroup in Niger and Chad. During Gerewol, men decorate themselves with makeup, feathers, and jewelry, performing mesmerizing dances to attract potential brides.

Marriage traditions vary: some unions are arranged within clans, while others result from elopement rituals (teegal). Bridewealth is paid in cattle, linking marriage to pastoral wealth.

Modern Challenges and Adaptation

Today, Fulani communities face growing challenges:

- Climate change reduces grazing lands and intensifies herder–farmer conflicts.

- Urbanization and national borders restrict nomadic routes.

- Stereotyping in the media has linked Fulani herders with conflict, though most remain peaceful traders and pastoralists.

In response, many Fulani are educating their children, engaging in modern business, and forming cultural associations to preserve their heritage.

Across Africa, Fulani leaders continue to promote peaceful coexistence and defend their identity in the modern era.

Bottom Line

@gimbalanke #foryourpage #foryou #malitiktok🇲🇱 #mali #guineenne224🇬🇳 #burkinatiktok🇧🇫 #gambia #fulfulde #camerountiktok🇨🇲 #nigeria #fulbe #fulani #poular #fula #mauritania #senegalaise_tik_tok #bani ♬ original sound – Mobbo Bari

The Fulani people have shaped Africa’s cultural and political landscape for centuries. From the pastoral trails of the Sahel to the mosques of Sokoto and Futa Jallon, their influence runs deep, rooted in faith, dignity, and movement.

They are a living bridge between tradition and modernity, between the desert and the city, and between Africa’s past and its evolving future.

Related Posts:

- 10 Facts About the Hausa People and Their Culture

- West African Architecture - A Journey Through…

- 6 West African Horse Breeds That Tell the Real Story…

- Cosmology of the Dogon People - Stars, Spirits & Creation

- Who Are the Kanuri People? A Cultural Introduction

- Exploring Lake Chad Basin - Travel, Culture, And…