In many rural West African communities, the moon continues to serve as a primary reference for marking time because it is a universally visible, reliable, and culturally embedded natural cycle.

Table of Contents

ToggleLong before the introduction of mechanical clocks and Western calendars, the lunar cycle provided a consistent and easily observable pattern for structuring agricultural activities, religious ceremonies, fishing expeditions, and social events.

Even today, in areas where access to formal education, electricity, and digital devices is limited, the moon remains a practical and trusted tool for timekeeping.

Its phases are used to determine planting and harvesting periods, schedule community markets, organize traditional festivals, and even dictate fishing and hunting strategies.

This reliance persists not only because of tradition, but also because the lunar cycle aligns closely with environmental patterns and seasonal changes that affect daily life in rural West Africa.

Historical Roots of Lunar Timekeeping in West Africa

The use of the moon to measure time in West Africa dates back thousands of years, predating contact with Islamic and European time systems.

The lunar cycle, which spans approximately 29.5 days from one new moon to the next, provided an accessible and repeatable way to divide the year into months without the need for written records or instruments.

Many ethnic groups, such as the Fulani, Dogon, and Mandinka, developed intricate systems of lunar observation, often assigning each moon cycle a name corresponding to agricultural, climatic, or social events.

For example, the Dogon calendar traditionally includes months like the “Seed Planting Moon” and the “Harvest Moon,” directly linking celestial observation to survival needs.

This approach was practical for communities whose economies depended heavily on subsistence farming, fishing, and livestock herding. In the absence of mechanical clocks, villagers could simply observe the moon’s visible changes, its waxing, full, and waning phases, to know how far they were into the month.

The Lunar Cycle as a Functional Calendar

The moon provides a complete cycle roughly every 29.5 days, and rural communities often align their “months” with this natural rhythm. In many cases, twelve or thirteen lunar months make up a year, depending on whether a leap month is added to keep the lunar year in step with the solar year.

The phases are not just abstract markers; they are tied to specific tasks:

Lunar Phase

Local Observation Method

Common Activities Scheduled in Rural West Africa

New Moon

Thin crescent seen just after sunset

Start of a new month; ritual cleansing; setting planting dates

First Quarter

The Moon is visible in the west after sunset

Light evening fieldwork; preparation for market days

Full Moon

Brightest night, visible all night

Night fishing, night markets, wedding ceremonies, and initiation rites

Last Quarter

The Moon is visible in the early morning

Preparing fields for next planting; community meetings

Because the moon’s light changes predictably, activities that benefit from extended natural illumination, like fishing in shallow waters or nighttime harvesting, are often scheduled around the full moon.

Conversely, activities requiring darkness, such as certain religious rituals, may be planned for the new moon.

Agriculture and the Moon

In rural West Africa, agriculture is tightly bound to environmental cues, and the moon plays a major role in seasonal decision-making. Farmers often plant seeds according to specific moon phases, believing (and in some cases observing) that germination rates, crop vigor, and pest resistance are affected by lunar timing.

For example, in some communities in Mali and Senegal, crops that grow above ground (such as millet, maize, and groundnuts) are traditionally planted during the waxing moon, when the moon is increasing in brightness.

Root crops like yams and cassava may be planted during the waning moon. These practices are often reinforced by generational knowledge passed down through oral tradition, and in many cases, farmers report that timing with the moon aligns well with seasonal rainfall patterns.

In addition, the lunar calendar often marks important agricultural festivals. Post-harvest celebrations, seed blessing ceremonies, and collective weeding days are set according to specific moon phases, ensuring that the community works in sync.

Religious and Spiritual Importance

The moon also has a central place in the spiritual life of many rural West African communities.

Islamic lunar months, such as Ramadan and the month of Hajj, are determined entirely by moon sightings, and in predominantly Muslim regions like northern Nigeria, Senegal, and Mauritania, local religious leaders announce the start of months after visually confirming the new crescent.

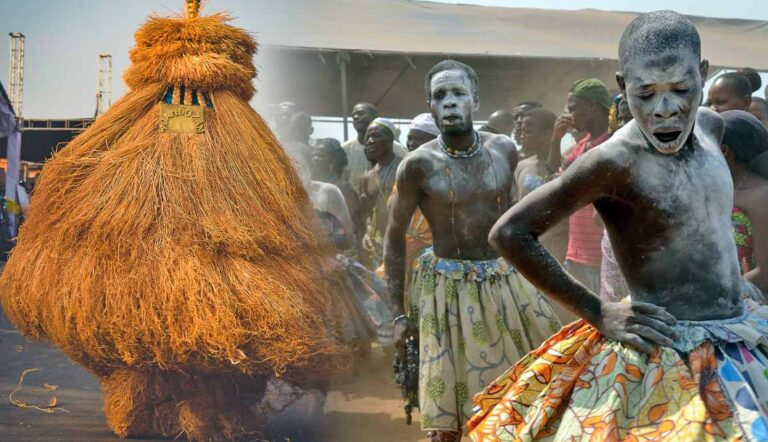

Traditional African religions also incorporate lunar phases into their ceremonial calendars. Among the Yoruba, certain deities are honored during specific moon phases, and rituals may require the symbolic presence of the full moon.

The Mende people of Sierra Leone use lunar cycles to guide initiation ceremonies into secret societies such as the Poro and Sande, which play a central role in community governance and moral education.

Christian communities in rural Liberia, Ghana, and Sierra Leone also integrate lunar reckoning, particularly for scheduling Easter-related events and local saints’ feast days that may be adapted from older lunar traditions.

The Moon and Fishing Communities

In West African fishing villages along the coasts of Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Senegal, the moon dictates not only the timing of fishing trips but also the type of catch targeted.

The brightness of the full moon often makes certain species more difficult to catch because fish can see nets more clearly. Conversely, during the new moon, darker waters favor the capture of species like sardines and anchovies, which are drawn to lantern lights on fishing boats.

Tidal patterns, which are directly influenced by the moon’s gravitational pull, are also well understood by these communities. Knowledge of when spring tides (the highest high tides) occur allows fishermen to plan for easier boat launches and landings, as well as for shellfish collection during low tides.

Social Organization and Market Days

In many rural regions, periodic markets, held every four, seven, or eight days, are timed according to the lunar cycle to maintain consistency. A market might always be held, for example, three days before the full moon, ensuring that traders and buyers can use moonlight for overnight travel.

Weddings, funerals, and other large gatherings may also be scheduled to coincide with a waxing or full moon, when travel between villages is easier at night. These practices have practical benefits: fewer accidents on unlit paths, greater security in numbers, and more time for festivities without relying on artificial lighting.

The Lunar Year vs. the Solar Year

@wunmiaramiji The months are approximate as lunar calendar doesn’t exactly sync with solar calendar. I need to know my local landscape well enough to name my own months. I fear I’d only come up with “October would be when the oil companies dump their waste into the river and pray no one will notice” 💀 #fyp #decolonization #indigenous #nature #moon #spirituality #nature ♬ original sound – Wunmi Aramiji

One challenge of lunar timekeeping is that a lunar year (354 days) is about 11 days shorter than the solar year (365 days). Many rural communities adjust for this drift by adding an extra lunar month every two or three years, ensuring that agricultural and festival seasons remain aligned with climate patterns.

Some areas blend lunar and solar reckoning, using the moon for monthly and weekly scheduling but aligning planting seasons with the solar-based rainy and dry seasons. This hybrid system allows communities to keep traditional cultural timing while benefiting from solar-based agricultural predictability.

Modern Influences and Continued Relevance

While mobile phones, radios, and printed calendars are increasingly available, they have not fully replaced lunar reckoning in rural areas. This is partly due to the resilience of cultural habits and partly because the moon is still visible and requires no technology to use.

For example, in rural Guinea-Bissau, even households with smartphones often discuss upcoming events in terms of moon phases, because these references are universally understood regardless of literacy or language.

Similarly, in rural Niger, elders may disregard the printed date of Ramadan until a local moon sighting confirms it, reinforcing the authority of traditional timekeepers.

Bottom Line

The moon still dictates time in many rural West African communities because it is an accessible, reliable, and culturally entrenched system that aligns closely with environmental rhythms.

From planting fields and organizing markets to guiding fishing trips and marking sacred ceremonies, lunar observation remains a practical tool in daily life where technology may be limited or less relevant.

While modernization is influencing timekeeping, the moon’s visibility and deep cultural roots ensure its ongoing role as a natural, community-wide clock. In regions where survival and tradition are intertwined, the moon is not just a symbol—it is still an essential part of how life is organized.

Related Posts:

- Traditional West African Plants Still Used in Global…

- Ancient African Traditions That Are Still Thriving Today

- Best Time To Visit Tunisia In 2026 - Weather By…

- Why West Africa’s Entertainment Scene Is a Global…

- Why African Women’s Skin Ages So Well - And What You…

- Why Every African Folk Tale Has a Trickster: Lessons…