In 1324, a ruler stepped out of West Africa with so much gold and so many attendants that people from Cairo to the Levant struggled to believe what they were seeing. Mansa Musa, the emperor of Mali, decided to make the pilgrimage to Mecca and turned the event into a moving capital.

Table of Contents

ToggleHis caravan crossed thousands of kilometers, passed through some of the hardest terrain on Earth, and left chroniclers scrambling for words. Nobody expected a procession that large to roll out of the Sahel. Nobody expected a royal hajj that felt like an entire state on the move.

The picture we have today comes from Arabic witnesses, later scholars in Timbuktu, cartographers who sketched Musa with a gold orb in hand, and modern historians who patiently stitched the puzzle pieces back together.

When everything is placed side by side, the journey becomes one of the most impressive logistical operations in the medieval world.

Mali Before the Caravan

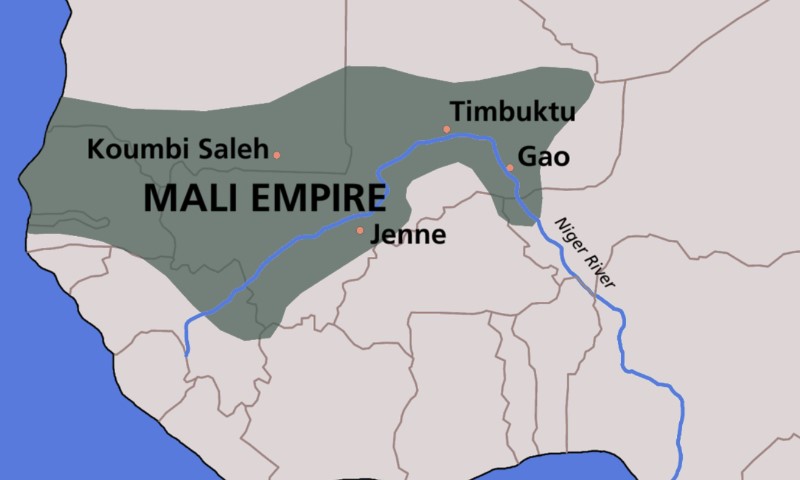

Before Musa ever packed a single camel with gold dust, Mali stood as a powerhouse across a broad belt of the western Sahel. The empire reached across what is now Mali, Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, and Guinea. Its prosperity rested not on chance but on a well-built political economy that fed the throne both wealth and authority.

The Niger River basin, Sahel towns, and desert edges formed a network of markets that funneled goods north and south. Merchants moved between savanna towns and Saharan oases carrying metalwork, salt, horses, textiles, and, of course, gold. Musa inherited a system that rewarded tight control of trade corridors and rewarded a ruler willing to enforce it.

Control of Trans Saharan Trade Routes

Trade corridors shaped the empire’s power. Gold flowed north toward cities of the Maghreb. Salt bricks from the Sahara moved south to support life in the Sahel. Horses traveled south as prized prestige goods.

Caravans coming from regions like Bambuk and Bure delivered gold to royal agents who taxed, counted, and distributed it. The ruler kept the largest share. Tribute from vassal territories added more. Every merchant who crossed the Sahel knew that Mali owned the southern gate of the desert.

Monopoly Over Gold Exports

Arabic chroniclers recorded that large nuggets of gold were reserved for the ruler alone, while traders used dust. Even if those rules varied from town to town, the core idea holds. The court concentrated gold.

That meant the emperor could outfit armies, build cities, reward allies, and, when he wanted, assemble a caravan that made even Cairo’s elite sit up straighter.

Musa’s wealth did not exist in a vacuum. It came from organized mining, taxation, tribute networks and control over movement. By the time he planned his pilgrimage, gold reserves were deep enough to support a spectacle few had ever seen.

Growing Urban and Intellectual Centers

Cities like Timbuktu and Gao were picking up momentum. Libraries grew. Manuscripts circulated. Scholars traveled in and out of the region.

When Musa decided to head toward Mecca, he represented a state already leaning into intellectual life. His pilgrimage amplified that development after he returned.

The growth of Timbuktu’s reputation in later centuries has roots in this period. Musa’s investment in religious and scholarly institutions after his return sharpened the city’s profile, eventually turning it into one of the best-known intellectual hubs in the Islamic world.

How We Know About Mansa Musa’s Journey

Nobody in Mali produced a diary of the pilgrimage. Information survives because writers in Cairo and later towns of the Sahel found the event impossible to ignore. Their notes, combined with archaeology and scholarship, give a detailed enough picture for historians to reconstruct the scale.

Shihab al-Din al-Umari spoke with Egyptians who witnessed the caravan. Ibn Khaldun added context and political detail in his writings. Timbuktu scholars in the seventeenth century wrote about Mali’s dynasties in chronicles that preserved fragments of older traditions.

European mapmakers absorbed the stories and placed Musa on their atlases, turning him into a symbol of West African wealth.

Modern historians compare every available source and align them with what is known about trans Saharan caravans. The numbers may drift from one account to another, but the basic shape stays consistent. Musa’s caravan was enormous.

Planning an Imperial Hajj

A ruler did not simply decide one morning to march out of Mali with thousands of people. Musa planned for years. He had religious duties, political goals, and economic interests rolled into one mission.

The pilgrimage allowed him to show devotion, strengthen ties with the Mamluk world and establish Mali’s reputation among scholars and merchants along the route.

The preparations were massive. Gold had to be weighed and packed. Horses had to be selected for noble riders. Camels had to be gathered from multiple regions. Tents needed stitching. Water containers, grain caravans, dried meat, fodder, and textiles all had to be secured. Guides from regions across the Sahel and Sahara needed to be hired.

Musa even appointed his son to rule in his absence, a sign that he knew the journey would swallow many months.

When he finally departed, he brought not a royal entourage but an entire political order on the move.

Mapping the Route Across the Sahara

Musa’s path carried him from the savanna to the Sahel, then into the deep desert. The outline of the route appears repeatedly in Arabic accounts.

The journey started near the Niger River basin, moved north toward Walata, and then continued through a long chain of oases toward the Nile.

From the Niger Basin to Walata

The early stretch moved through grasslands and scrub where wells were more reliable. Even there, feeding tens of thousands of travelers required negotiation with village leaders.

Grain stores were purchased in advance. Pastures were surveyed for animals. Musa turned those towns into logistical partners.

Into the Sahara

After Walata, the desert swallowed the horizon. The caravan crossed dunes, gravel plains, and wind-carved rock. Movement depended on precise scheduling. A large caravan could not wander. Wells had to be hit on time. Oases needed warning. Sandstorms forced halts. The journey tested every point of the empire’s organizational system.

Typical caravans in the region sometimes used thousands of camels. Musa added royal guards, musicians, religious scholars, gold carriers, slaves, and high-ranking officials. The result exceeded the scale of normal trade caravans.

Arrival in Cairo

When the caravan reached the Nile valley, Musa camped near Giza before entering Cairo. His arrival sparked a wave of curiosity. The Mamluk sultan received him formally, and Musa surprised many witnesses with the richness of his gifts and the number of attendants surrounding him.

From Cairo, the caravan joined established hajj routes through the Levant and the Hijaz. Those paths were well known and consistently used by pilgrims across the Islamic world. Musa continued with the same level of ceremony, eventually reaching Mecca.

Many modern travelers who retrace parts of Musa’s route through the Nile valley often rely on guided Egypt tours to get a structured sense of how his arrival reshaped Cairo’s political and commercial rhythm.

The Full Scale of the Royal Caravan

Writers disagree on exact numbers, but Arabic and later West African accounts consistently describe a crowd far larger than anything seen on ordinary pilgrimages.

Many historians repeat the line that Musa brought around sixty thousand people. Some speak of twelve thousand enslaved attendants. Others mention five hundred carriers of golden staffs. Even with caution about exaggeration, the picture is overwhelming. Musa traveled with a moving city.

Composition of the Caravan

The caravan brought together multiple layers of Malian society:

- Courtiers and nobles

- Legal scholars, imams and reciters

- Soldiers from core provinces

- Wealthy merchants

- Translators for various Saharan languages

- Artisans and tent workers

- Enslaved porters handling heavy labor

Animals and Cargo

Arabic accounts frequently mention eighty to one hundred camels carrying gold. Some modern summaries translate that into roughly three hundred pounds of gold per camel.

Estimates of total gold carried sometimes reach eighteen metric tons, though modern scholars treat such figures as approximate.

Other animals carried food, tents, water containers, ceramics, grain and tools. Horses for elite riders traveled with the group. Animals for sacrifice and consumption moved with the caravan as well. The entire assembly required continuous resupply from oases and Sahel towns.

A Comparison Table

| Feature | Large Saharan Caravan | Reported Scale of Musa’s Caravan |

| Camels | 1,000 on average | 80 to 100 gold camels plus many more for supplies |

| People | Hundreds to a few thousand | Around 60,000 |

| Gold Per Camel | Mixed trade goods | Around 136 kg of gold dust |

| Purpose | Commerce or pilgrimage | Royal pilgrimage, diplomacy, spectacle |

The numbers may not be perfect. They do not need to be. Every account agrees on one point. Musa’s caravan sat at the extreme top of what the Sahara could realistically support.

Logistics of Moving a Traveling City

Moving thousands of humans and animals through the Sahara required precise coordination. The desert punished mistakes. Musa relied on wealth, skilled guides and a complex support system.

Water and Food

Oases prepared for the caravan long before it arrived. Wells were cleared. Animals were watered in stages. Musa’s officials paid high prices for grain and dates. Dried meat traveled in reserve containers. Runners moved ahead to check water levels.

Supplies were consumed at a rate that could drain a small settlement. Local economies experienced sudden spikes in demand. Musa paid for those strains in gold and textiles, which helped smooth relations.

Security

Gold attracted danger, but Musa arrived with troops capable of protecting the caravan. Escorts included cavalry from Mali’s central provinces, infantry trained for long marches, and hired guards familiar with desert terrain.

Security within the caravan mattered as well. Gold reserves had to be monitored. Camp discipline had to be enforced.

Time and Pace

A typical day in the desert involved slow, steady progress. Caravans traveled in the early morning and late afternoon to avoid heat. Movement in the Sahara required constant awareness of wind, dunes, and water intervals. The outbound trip and the return together likely consumed more than a year.

Cairo’s Reaction and the Ripple Effects

When Musa reached Cairo, he entered a world that already knew how to handle wealthy pilgrims. Even so, the scale of his currency, attendants and generosity startled Egyptian observers.

He camped near Giza, then crossed the Nile to meet the sultan al Nasir Muhammad. Accounts describe a disagreement over greeting protocols, eventually settled through negotiation. Once those formalities were handled, gifts flowed. Musa distributed large amounts of gold as alms. He paid high prices for goods and supported scholars and local institutions during his stay.

Egyptian writers later linked a drop in the value of gold to Musa’s generosity. Some later stories claim a dramatic collapse in the economy. Modern monetary historians, including Warren Schultz, treat the shift as noticeable but not catastrophic. The change still impressed contemporary eyewitnesses, who had never seen a ruler distribute gold so freely.

Diplomatically, Musa succeeded. Mali became a recognized presence in the imagination of merchants and scholars across North Africa and the Middle East.

Return to Mali and Lasting Influence

After completing the pilgrimage, Musa made his way back across the desert. Some accounts suggest he borrowed gold in Egypt after spending more than planned. Borrowing or not, he returned with architects, manuscripts, scholars, and new ideas for shaping Mali’s urban landscape.

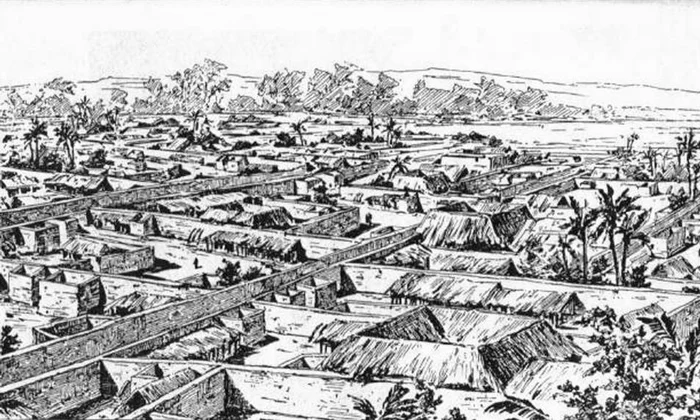

Architectural Legacy

Musa funded large construction projects after his return. The most famous include the Djinguereber Mosque in Timbuktu and major mosques in Gao. The arrival of an Andalusian architect known as Abu Ishaq al Sahili is often associated with this building wave.

Scholarly Growth

Timbuktu gained new energy from Musa’s patronage. Libraries expanded. Scholars traveled south from North Africa. Manuscripts accumulated in family collections. Mali began to stand out as a center of Islamic learning, with Musa’s hajj acting as a catalyst.

A New Global Image

Cartographers in Europe placed Musa on their maps. The Catalan Atlas of 1375 shows him crowned, holding a gold orb. That image traveled widely and shaped outside views of West Africa. Musa became the figure that represented an entire region to audiences who had never crossed the Sahara.

Why Mansa Musa’s Caravan Still Matters

The story offers a rare look at how power, faith, trade, and logistics worked together in medieval Africa. Musa’s pilgrimage reveals West Africa not as a distant corner but as a region woven into larger Islamic networks.

It shows how desert routes supported enormous movements of people and currency. It highlights the role of gold in shaping diplomacy. It demonstrates how a single journey could expand intellectual life, stimulate urban development, and reshape how distant lands pictured the Sahel.

Mansa Musa’s caravan remains one of the clearest windows into a world connected by sand, faith and gold, where the Sahara functioned not as a wall but as a highway for those who had the resources and discipline to cross it.

Related Posts:

- West African Architecture - A Journey Through…

- Mauritania vs Morocco - Which Country Is Better for…

- Sacred Baobab Tree - Myths, Medicine, and Symbolism…

- 6 West African Horse Breeds That Tell the Real Story…

- How Islam and Christianity Spread Across West Africa

- Can You Drive Across Africa from West to East Safely?