“Human speech is like a cracked cauldron on which we bang out tunes …”

Table of Contents

Toggle― Gustave Flaubert

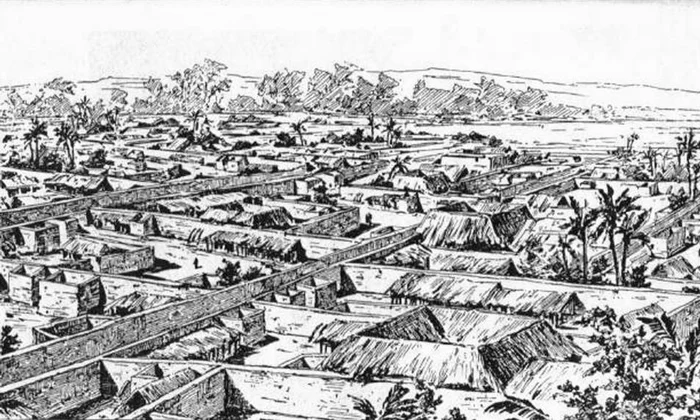

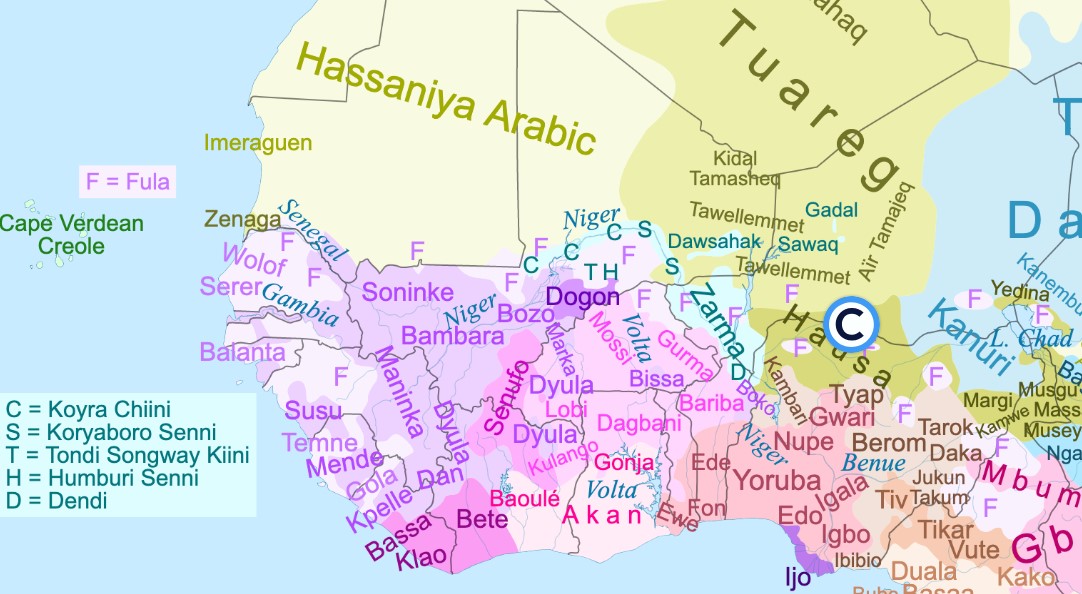

So prosodic are the primarily tonal languages of West Africa, that most speech reverberates far, able to be beautifully mimicked, rhythmically reproduced, and literally “banged out” through the elaborate talking drum motifs inherent to this region of the world. This rise and fall of pitch are characteristic of West African languages― with some non-tonal language exceptions like Fula, Wolof, and Koyra Chiini ― within its three major language clusters: Niger-Congo (i.e. Ewe, Igbo, Malinké, Yoruba), Afroasiatic (i.e. Hausa), and Nilo-Saharan (i.e. Songhay).

West Africa, with its 500-plus indigenous languages, eclipses other regions of the world with its incredible linguistic diversity and density.

And if it is true that “whoever acquires another language possesses another soul”, multilingual West Africans possess many. Each acquired language has its own deep history, identity, and unique grammatical particularities, from the complex pronoun systems of Yoruba and Wolof to the verb serialization of Kwa and Nupe. Each of these languages holds unique power in a corner of the world where words, especially the spoken word, “through the vibrations that it sets in motion, activates and propels all things …

The Power of Spoken Language in West Africa

Words, and the interstitial silences between them, are potent in traditional West Africa ― handled with care by the ancestral lineage of griots, by storytellers, by sages ― prevailing across generations through the art of orature.

“The African child until publicly named, the incantation until given voice, the art or the craft until accompanied by speech is not truly ‘brought forth’ …”

― Cultures of West Africa

Symbolic Languages of West Africa

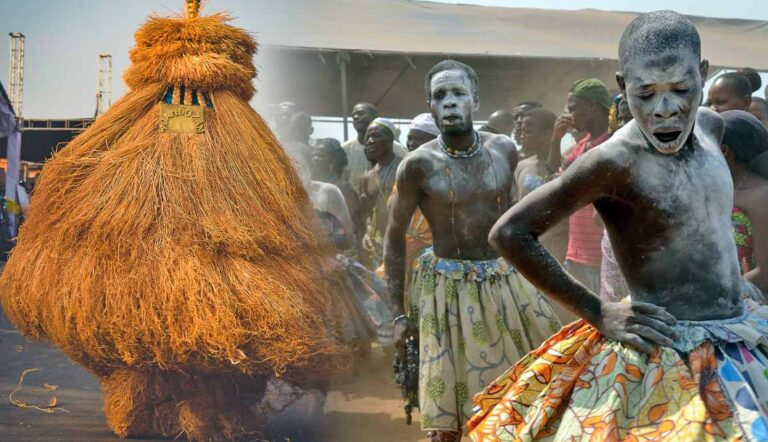

Just as drums were endowed with the gift of “eloquent talking” by the Yoruba Orisha Ayangalu ― ‘Oku ewure ti n f’ ohun bi eniyan”, the skin of a dead goat speaks like humans ― human words and daylight were woven into the interstices of bands of fabric by the Dogon’s primordial Nommo.

And so it goes that fabric, as well as other supports such as pottery, calabashes, and masks, were the original canvases for other simultaneous, more visual West African languages, from hand-stamped Ashanti and Baoulé adinkra symbols to ancient Ekoi, Efik and Igbo nsibidi iconography.

Drawn in the red Sahelian dust, the thousand or so encoded Nsibidi symbols communicate thought instantaneously. Traced skyward, in the air, Nsibidi transforms into a language of gesture, as expressive as indigenous and independently-developed sign languages like Akan Adamorobe or Adasl, Bambara LaSiMa, or an array of others that have developed, in isolation, in small villages with high incidents of deafness.

Today, those same visual symbols have inspired many contemporary forms of cultural expression. One creative example includes Custom PVC Keychains that feature adinkra or nsibidi motifs. These small items make it possible to carry ancestral identity into modern spaces like classrooms, markets, or offices, preserving traditional forms in practical, everyday objects.

When African Languages are Transcribed

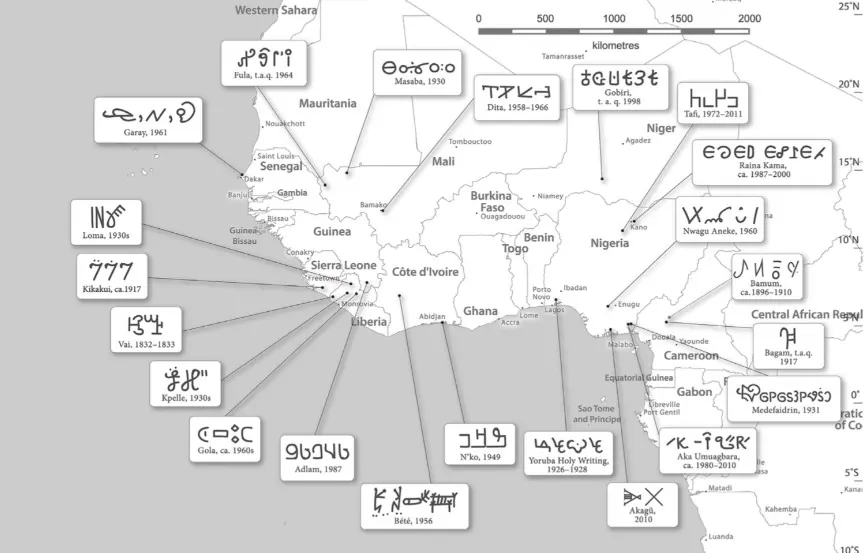

Drawing on this rich, indigenous, pictorial, gestural, and highly illustrative culture, West Africa has been the fertile ground out of which home-grown scripts have blossomed: the invention of Vai, a Liberian script created ca. 1833, of Masaba (a 1930s Malian writing system), or the recent Akagü script, repurposed from an indigenous graphic code (Nigeria, 2010).

“Few regions of the world rival West Africa for the sheer scale, diversity and dynamism of its indigenous writing traditions.”

― Piers Kelly

The most successful West African writing system to date is undoubtedly N’ko, created for the mutually intelligible Mandé languages of Malinke, Bambara, Mandengo, Dioula and Wankara (Côte d’Ivoire, 1949).

Related Posts: